An Interview with Alison Stagner, Poet & Author of “The Thing That Brought the Shadow Here”

November 9, 2020

By Gabriela Denise Frank

A minute into the interview, Alison Stagner said, “When an image strikes me as really beautiful, I immediately want to undercut that. For me, beauty is about disruption.”

I was already looking forward to speaking with her after reading her book, but my heart flip-flopped when she said this. We were in for a juicy conversation.

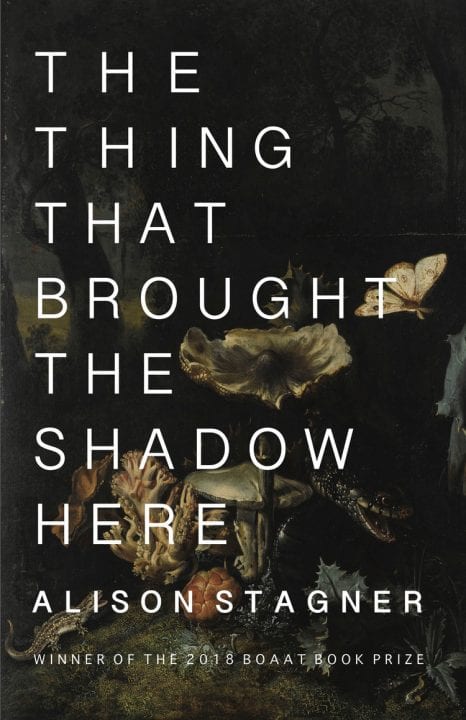

Alison serves as SAL’s Communications Manager and she’s the author of The Thing That Brought the Shadow Here, a collection of poems published by BOAAT Press, selected by rockstar-bard Nick Flynn as the winner of the 2018 BOAAT Book Prize. We spoke shortly after her book was released.

Reading The Thing That Brought the Shadow Here brought to mind the Picasso quote that a great painting comes together, just barely. Alison’s poems are deft and tricksy, they travel loosely, trading in slippage and incantation. Objects appear solid, secured with red grosgrain ribbon, then twist away into smoldering wicks of taper candles snuffed by ghost-breath. Her tonal approach to beauty as disruption, a thing that unsettles rather than soothes, links this collection of poems on loss, love, and longing, ensnaring its subjects (and readers) like ivy.

Ethereal as their joinery is, I kept trying to touch the meaning of Alison’s poems with the blunt force of my hands. Each time I felt close to solving her riddles, I took a quarter turn and looked again from a different angle, finding more questions than answers.

In his introduction, Flynn identifies a sense of restlessness in Alison’s poems, which he describes as thoughtful and broken, seeking yet confounded, carrying him into collision with a mythic, imagined past. “Like any true poem, its [meaning] cannot be paraphrased,” he writes.

That was the folly I attempted with my careful reading and underlining, scribbling notes in the margins. Despite his warning, I was reading Alison’s work with an intent to define, to pinpoint, to pin down the ineffable with strokes of soft pencil lead. Silly rabbit. I needed to stop pestering her poems, demanding to know what they were about.

The Thing That Brought the Shadow Here is crafted to work more like a mirror than an oracle. It doesn’t foretell or define. Instead, it reflects what’s haunting the heart of each seeker, holographic symbols only they can see. Each poem is a room in the dollhouse of the mind, and Alison paints the cracked walls with fine brushes and surprising colors—lung-cage white, the yellow of a vintage canary figurine—placing objects from the past into the present.

This co-mingling of modern and antiquary creates a shifting sense of time. I longed to hold the secrets revealed inside, but as the title (which I love) suggests, the book’s mille-feuille of fateful attraction, beguiling and unearthly, keeps to itself. Still, I sought to know: what is the thing that cannot be named? We never see it, but we feel its presence—we’re standing in its shadow after all!

Alison chuckled at my enthusiasm and confessed that she hates coming up with titles.

“Someone once said in a workshop, ‘You can’t use the word thing in a poem, especially not in the title, and I was, like, ‘Well….’ I love the word thing because in this poem, in the title, you really do have to interrogate every part of that phrase. Like, what is the thing? What’s the shadow? Where is here?” she said.

Though these poems were written a few years ago as part of Alison’s MFA, the looming quality of The Thing That Brought the Shadow Here feels eerily prescient. We are searching, as Alison’s poems do, for something solid to hold in a year that’s revealed the paper-thin veneer of our illusions. At the edge of our peripheral vision, we feel the life-force of a thing gathering in the mist—a negative capability we’re struggling to make peace with. This boundless uncertainty has always been here, but now we perceive its shadow. Pandemic life is forcing us to walk maddeningly slow, often alone, through the miasma of a long and unfolding middle, muttering unanswerable questions, pestering each other to know when life will be different.

The poet John Keats defined a great thinker as one “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” A poet’s power, then, resides in their ability to surf waves of change rather than cling to buoys, hoping for divine rescue. In that spirit, Alison’s poems serve as a guide to the unknown, a cloaked figure pointing toward an uncharted dimension we must map for ourselves. Her book suggests that we hold everything loosely: the path we’re following and our method of travel; our companions, our speed, our progress—even the desired destination.

Keats famously noted, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” The pilgrimage to and inquiry of a thing, rather than its conclusion, form its definition. Meanwhile, we’re struggling with the precarious notion of aliveness—unspeakably tender, unpredictably ferocious—having confused distraction with change and stasis with control. In this expanding moment, we’re grasping to comprehend an overlay of paradoxes, an endless continuity whose infinite, gossamer connections become the point.

The following conversation has been excerpted from a longer interview.

Gabriela Frank: Congratulations, Alison, on The Thing That Brought the Shadow Here, published by BOAAT Press and selected by Nick Flynn as the winner of the 2018 BOAAT Book Prize! These poems feel beautiful and unsafe, the way fairy tales do. Images appear real enough to hold, then disappear in a wisp of smoke. Can you talk about what drove this collection?

Alison Stagner: My approach to poetry and writing has always been that a poem isn’t a vessel to hold your argument or a container for your ideas. Whenever I go to the page, there’s a question within myself I want answered. That’s why there’s a restlessness to the images or a tonal cognitive dissonance. I get momentarily obsessed with an image that strikes me as really beautiful, then I immediately want to undercut that. For me, beauty is about disruption.

One of the main things I was thinking about when writing these poems—which aren’t autobiographical—was my father, who died when I was a baby. I don’t have any memories of him. I became aware at a young age of this sort of double-self. I was having thoughts and emotions about him and trying to reconstruct who he was in my mind—trying to connect with him through the stories of other people, through things he left behind, books he loved, philosophies he had about his life—and realized I couldn’t mourn him in the way my mother and my brother mourned him. They remembered him, and I was always inventing him in my head. Because of that, I have these thoughts, but they’re also not my thoughts. They’re not attached to reality.

While I was writing this I was thinking a lot about danger, which appears in every poem in some way. I was thinking about what violence is—a language someone uses when they don’t have another kind of language to express themselves. I think violence is the currency of our lives. If you want to distance yourself from violence, you have to divest all of your money, your property, the food that you eat, the politics you support. Basically, you can’t. That’s something I constantly returned to, drafting all of these poems, along with the deadline of having to write for workshops.

Gabriela: They were written during a year or two?

Alison: Yes—two. I did the MFA program at the University of Washington and all of the poems, except for a couple I started before the program, were workshopped. What came out of that program went into the book.

Gabriela: Your poems call to mind the Picasso quote, A great painting comes together, just barely. The title itself, The Thing That Brought the Shadow Here, encapsulates a sense of almost or just barely. What is the thing? We don’t know, but we feel its shadow hanging overhead. We’re standing in its darkness.

Alison: I’m glad you think so! [Laughs] I’m very anxious about titles. This one felt right. There is slipperiness to it that I love. Someone once said in a workshop, “You can’t use the word thing in a poem, especially not in the title,” and I was, like, “Well….” I love the word thing because in this poem, in the title, you really do have to interrogate every part of that phrase. Like, what is the thing? What’s the shadow? Where is here?

Gabriela: When arranging these poems, did you have a sense of the shape of the book in four parts, or is that something that came out over time?

Alison: Honestly, it’s chance that it ended up that way. The parts are there as a pause. The real challenge of a book, where it’s not a project book, is that it’s not about one subject. There’s not a through-line. I liked the four-part structure because lands between the traditional structure of a novel—beginning, middle, end—and a five-act play. I’m always, like, do we need the fifth act?

The best piece of advice I got when thinking about structuring a manuscript was from Pimone Triplett, a poet in the University of Washington MFA program. She said, “Take every poem and assign an instrument to it, then try to build a symphony out of those instruments. When do you want something that sounds mournful and sad, like a cello? When do you want something playful to counterbalance that immediately afterwards, like a flute? When do you feel like you want a mysterious or creepy tone like an oboe?” No offense to oboists. I wrote at the top of each poem, flute, oboe, cello and laid them all out on the floor. I realized I needed a climactic section, and I needed to feel like there was some resolution by the end. I needed to introduce some themes at the beginning. I went in and tried to layer the instruments or tonalities of the poems. That’s where the four parts came from.

Gabriela: You and we come up a lot in these poems. Does you stand in for different people? Is there an intended listener or receiver for this collection?

Alison: It depends on the poem. A lot of times you means I. I’m talking to myself. Other times, I use you as a tonal trick. Like, you’re reading something on the page, then all of a sudden when someone directly references you, it’s like the page is staring back at you in a moment of self-awareness. The we and our reference a romantic relationship. This relationship is interwoven into some of the poems. It varies, but I hope there’s also room for it to be open to interpretation, like the I can be you, and the you can be I.

Gabriela: How do poems start for you?

Alison: I usually think about poems in three parts: the image, the sound or musicality, and the rhetoric or argument—the meaning of what the syntax is building to. I’m drawn to objects, to the visual, first. When I start to write a poem, I’m struck with terrible anxiety; I feel like every time I start to write, I’ve completely forgotten how to write a poem. I’m like, “What’s the poem? How do we do this thing?” I feel like I’m inventing what poetry is for me all over again.

The easiest way into a poem is when I see something or read about an old machine that’s interesting to me, or see a piece of art. From there, the sounds build on each other. One word makes me think of another word, so there’s a musical affiliation. From all of that mess of sound and image, I can try to construct an argument or some sort of rhetoric around what I’m trying to say.

Gabriela: What is your process like? Do you write, leave a poem sit, come back—or write the whole draft before moving on to the next poem?

Alison: I’m poem-monogamous. I tend to only work on one at once, and hyper-focus on it and write it over a period of a day or a few days, then get feedback, if I’m getting feedback. Then I kind of abandon it, like, we break up and that’s it.

Gabriela: Did you go back and create tendrils that link the poems in this collection, since some were a year or two older than others, or did they mostly stay intact?

Alison: Some changed a little bit, but most of my edits were fussy syntactical edits. I like really long sentences, and I usually have to go back and clarify things. Readers will say, “I don’t understand the reference of the sentence,” then I’ll have to go back and edit. There are a lot of leitmotifs I return to over and over again, like the same kinds of natural images, the same kinds of colors.

Gabriela: Colors, yes! You paint with hues described as lung cage white and yellow as a vintage figurine of a canary. Can you talk about the role of color in your work?

Alison: Part of it is an attempt to be surprising. A rib cage is white, so I guess I’m picturing a skeleton in my head. [Laughs] Which is not something I sit around doing a lot—I’m not Byron. But it’s a particular kind of white. You can describe a color as off-white with slight tinges of blue, but that doesn’t have as much emotional weight as something more anchored to the real world. By getting extremely specific, like cherry-red velvet—your cherry-red is going to be completely different from my cherry-red when we both picture a cherry in our heads—you’re going to have a specific idea of what that color is for you.

Gabriela: You reference many people in your poems, some dead, others mythical: Oscar Wilde, Saint Francis, Albrecht Durer, Don Juan, the goddess Diana. Do these figures show up elsewhere in your work? What interests you about them?

Alison: They’re definitely fascinations, some ongoing. I love mythology and fairy tales because those stories are so strange. It’s feels like anything can happen and things really transform. I wrote some of the poems in Rome as part of the MFA program. St. Francis was a figure who haunted me when I went to the Italian town of Assisi—he’s the patron saint of that town and the patron saint of animals. There’s the story about the wolf of Gubbio, a village where people were being picked off, one by one. St. Francis spoke to the wolf and basically talked the wolf down. Stories like that stick with me. I ruminate on them and create little mythologies in my head. I grew up without religion, so I’m not approaching St. Francis from a religious lens.

Gabriela: That’s a good segue to my next question about the way your poems bring together the human body and the animal world. Bodies are broken, injured and cut, and the poems invoke an animal closeness that’s unsettling and gothic, like the line, a hollow space in our breasts the crows fly into. Can you talk about these amalgamations?

Alison: If you look at psychological studies about emotion, they show that emotion happens in the body rather than the mind. You have a physiological reaction to a stimulus—you start sweating or the hair on your arm raises or your heart rate speeds—all of those physiological sensations are actually your emotions in their nascent state. It’s not until your mind starts processing what your body is feeling in reaction to a stimulus that you begin to say, “I feel sad because I watched a sad movie.” You actually feel the sadness before you interpret why it is you’re feeling that way.

Rick Kenney, my thesis advisor in the MFA program, talked to us about how poetry is tied in a special way to the body. He talked about using poetry and the tools of poetry to engage the animal body before you start engaging the brain. I don’t write in form, but something as simple as a rhyme scheme or meter will produce a sense of rhythm, and that rhythm might cause your body to have a physiological reaction. I love that idea. Part of that, for me, is the mystery of poetry. Why am I so drawn to poetry? Because a good poem will literally raise the hair on my arms. That’s the magic of language, that we can produce an actual, physical reaction in the world. Words aren’t just words. They can raise the hair on your arms.

Gabriela: It’s true, a poem can make the body tingle! I love how, at the end of the collection, you leave us with a question rather than tying everything up neatly. Do you feel like you found some answers in writing these poems, or came to a different place?

Alison: I must have because I don’t feel like writing about the same subjects. There must be something I’ve worked through in the process of writing. I don’t think it necessarily means I came to an answer or some new way of looking at the world. It’s more, like, I took something I was feeling and held space for it and those feelings felt like they were being seen. That allowed me to let go of them.

Gabriela: What was your relationship to poetry growing up? Or, how did you grow up as a poet?

Alison: I grew up in St. Louis—actually, Kirkwood, Missouri, where Marianne Moore is from, but I don’t read her poems. I should, but they’re terrifying to me. I always loved my English teachers growing up; I wanted to make them happy. I loved everything they told me about the world and humanity, and I listened very carefully. I was pretty good at writing, but I’d never really saw myself as a creative writer. I wrote a few poems here and there when I was in elementary, middle, and high school, like you do, because English teachers make you write poems. I loved literature. I loved reading. I worked on a literary magazine in high school. I didn’t see myself as a poet. I still have trouble seeing myself as a poet.

When I went to college, I was an English major. I was really focused on rhetoric and argumentative writing. I loved essay writing—I wanted to sharpen that skill—and I was very grade-conscious. My friends, who were cooler than me, were creative writers, and it encouraged me to take a writing workshop with James D’Agostino. He had this very gentle approach to poetry, like, “We’re going to read only contemporary poetry and we’re going to have casual conversations about poems.” I didn’t know what I was going to do when I graduated from a tiny liberal arts college, and he was, like, “You should do an MFA.”

The poems I produced for that class became my portfolio for applying to MFAs. The first day of my very first workshop, the first thing the professor asked, besides our names, was, “Who did you study under?” I was the only kid whose school no one had heard of, and I didn’t study under any famous poets. I went in with no foundational knowledge of poetry. I couldn’t have told you the title of a single poem by Gertrude Stein. I learned a lot. And that’s my process. That was my experience becoming a writer. Trial by fire.

Gabriela: Who do you enjoy reading now?

Alison: Poets like Brigit Pegeen Kelly, who wrote songs and was not a very prolific writer, but I think one of the best poets of her generation. Lucie Brock-Broido is another influence. She wrote Master Letters Signed, A Hunger, and Stay, Illusion. She was brilliant. They come out of the tradition of Emily Dickinson, poets who operate in the realm of mysticism, where they have to be overwhelmed with forces beyond their control to gain a limited access to knowledge. That is the through-line I’ve taken in terms of writers who are my north stars. Their poems are all very close to magical incantations.

I just finished Jericho Brown’s The Tradition, which I’ve been meaning to read ever since he came SAL. Oh my, I love his book and I’m just obsessed with the way he uses the image of flowers and transposes images of flowers over images of Black men and Black boys. It’s powerful and really amazing. And, honestly, I’ve been reading a lot of cookbooks lately because I just can’t handle reality.

Gabriela: How does your work as a poet feed into what you do at SAL?

Alison: My work at SAL exposes me to a lot of great writers, some of whom I’ve never heard of before, some of whom I’ve loved forever. For me, as a writer, the primary thing is that I get to read as part of my job. I try to read at least one thing by everyone who comes through in our seasons. I’m reading widely in genre, more so than I would if I was left to my own devices. I’m reading a lot of diverse voices and I think it makes me stronger as a writer. The more you read, the better you write.

Gabriela Denise Frank is a literary artist whose work has appeared in galleries, storefronts, libraries, anthologies, magazines, podcasts, and online. Her essays and fiction have been published in True Story, Hunger Mountain, Bayou, Baltimore Review, Crab Creek Review, Pembroke, The Normal School, and The Rumpus. A Jack Straw Writer and Artist Trust EDGE alumna, Gabriela’s work is supported by 4Culture, Mineral School, Vermont Studio Center, Jack Straw, Invoking the Pause, and the Civita Institute. www.gabrieladenisefrank.com

Gabriela Denise Frank is a literary artist whose work has appeared in galleries, storefronts, libraries, anthologies, magazines, podcasts, and online. Her essays and fiction have been published in True Story, Hunger Mountain, Bayou, Baltimore Review, Crab Creek Review, Pembroke, The Normal School, and The Rumpus. A Jack Straw Writer and Artist Trust EDGE alumna, Gabriela’s work is supported by 4Culture, Mineral School, Vermont Studio Center, Jack Straw, Invoking the Pause, and the Civita Institute. www.gabrieladenisefrank.com