Readers as Aliens: Reading Mary Ruefle’s Poetry

November 12, 2019

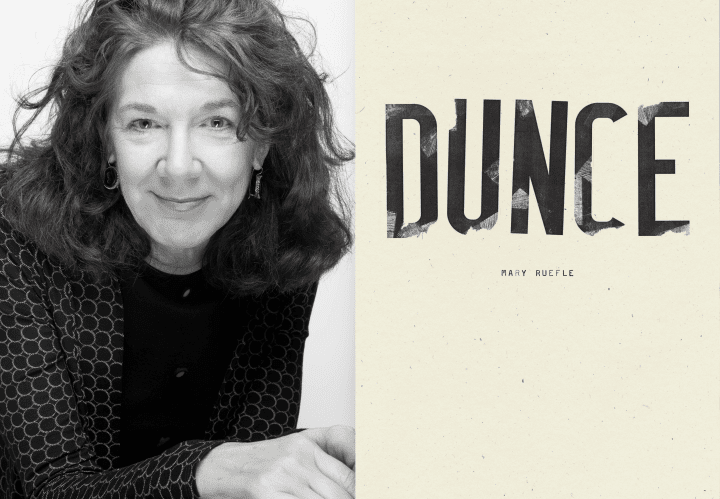

On Thursday, November 21, 2019, Seattle Arts & Lectures will present a reading with Mary Ruefle at Broadway Performance Hall in Capitol Hill. Mary Ruefle has published over ten collections of poetry. Below, local writer Bianca Glinskas reveals three favorite Ruefle poems and what they tell us about the reader and the writer.

By Bianca Glinskas

The Victorian house was in the middle of Downtown Denver; its low, creme-colored, ornate ceilings, scratched, creaking floorboards, and velvet, vintage furniture made the atmosphere feel antique and intimate. We met weekly in the parlor, a cozy space where we sat at a large, dark wooden table. I remember the thought and care that went into that packet of poems (I still have it somewhere, three moves later), each piece selected, scanned and compiled; we read, re-read, discussed, and flipped through its pages. The first fluffy white flakes of Winter fell slantways outside. Among these, was Mary Ruefle’s poem “Genesis.”

Oh, I said, this is going to be.

And it was.

Oh, I said, this will never happen.

But it did.

And a purple fog descended upon the land.

The roots of trees curled up.

The world was divided into two countries.

Every photograph taken in the first was of people.

Every photograph taken in the second showed none.

All of the girl children were named And.

All of the boy children named Then.

“Genesis” stood (and still stands) out to me for its peculiarity, humor, and spiritual contemplation. At first it profusely confused me. My initial reaction was similar to that of a puppy being asked to roll over: I tilted my head while wagging my tail. Re-reading to the poem again in Ruefle’s recently-released collection, Dunce (Wave Books 2019), I felt the tickle of déjà vu as the words reverberated through my life, returning to me by happy happenstance, seeming to almost collapse the space and time between, as if creating a portal or gateway to that snowy evening in the parlor.

There is an intentionality at work behind the creation of such a weird world, a bent logic at work structuring its strangeness. One secret behind this piece’s enjoyment lies, I think, in the way this poem challenges us as readers to surrender to the unknown. When I read “Genesis,” I gaze upon a foreign landscape, and yet I feel at ease, comfortable even. It is I who is alien here, though I do not feel alienated. We readers are somewhat stuck on our obsessive need to unravel the riddles, and to consume their answers. I think that sometimes it is better for us to go hungry looking for them. Now, re-reading the poem two years and several states away later, my puppy head tilts the other way, my tail still wagging. Ruefle’s writing maintains an awareness of the effects her words have on the reader, as if to nudge us: sometimes we must sit with what we do not know.

In Ruefle’s poem “The Bunny Gives Us a Lesson in Eternity,” we begin with a recognizable reality which evolves into an unrecognizable reality:

We are fond of the little bunny with the bent ear

who stands alone in the moonlight

reading what little text there is on the graves.

He looks quite desirable like that.

He looks like the center of the universe.

The bunny is a symbol for the power of interpretation and how the perception, the reputation of a thing, can shape, or in this case distort or delude that reality. This idea is embodied in the piece itself. The poem moves beyond the scope of itself, a shift so drastic it is almost a departure.

Look how his mouth moves mouthing the words

while the others are busy making more of him.

Soon the more will ask of him to write their love

letters and he will oblige, using the language

of our ancestors, those poor clouds in the ground,

beloved by us who have been standing here for hours,

a proud people after all.

I am reminded of another stanza from Mary Ruefle’s poem, “White Buttons”—which discusses reading as a transportive processes of discovery, comparing it to an out of body experience, right alongside the death of her parents; these subjects are tied together by their relationship with the tightrope, the known and unknown. It goes:

I like to read into things

as I am continually borne forward

in time by the winds like the snow

I think I am coming back

I feel shoulders

where a parrot could land

though a tree would be

as good a place as any

There it is again, the snow, the echo. The idea of returning to the body, beautifully and cleverly combining the metaphors of a talking bird landing and the rooted tree. Mary Ruefle’s poetry shows a brave intention: her commitment to confrontation, contemplation, and clarity. She thinks, feels, and breathes meaning into that space while we watch her powerful thought process—her assembly of logic and emotion, her surrender to what is and is not known or knowable.

The book that blew me away

held all the problems

of the world

and those of being alive

under my nose

but I felt far away from them

at the same time

reading is like that

Yes, it is. We readers are alien tightrope walkers—time traveling tourists, parrots transported outside of our trees.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bianca Glinskas is an emerging poet and literary journalist living in Seattle. She currently writes for Adroit Journal & Drizzle Review. Bianca hopes to complete an MFA in Poetry in the coming years.