Bittersweet: Ending My Time with TOPS Fifth Grade

February 9, 2018

By Laura Gamache, WITS Writer-in-Residence

The book said everything perishes

The book said that’s why we sing-Gregory Orr

Every WITS teaching residency has a beginning, middle and end, like the stories humans are wired to crave. As a primarily lyric poet, I tend to work with kids as if we’re outside the narrative arc until it is unavoidable that I will have to part with them. My WITS time with Ms. Danielle Alon’s two fifth grade L.A. classes at TOPS K-8 ends on Tuesday with our class reading celebrations. I want to hold onto some of our moments by singing about them here.

The first is about a boy who spent our first four weeks roaming the room, sharpening pencils to nubs, and distracting other kids in his table group—anything to avoid putting pencil to his own paper. This Tuesday, he hatched an idea, talked to me about it, wrote into it, made his it into a poem, shared it aloud in class, then folded it into a tiny square. “I want to take this home to show my parents,” he said. I ran to the copier so we wouldn’t lose that precious original.

A fellow WITS writer came to observe my afternoon class, and we ran into this boy in the hall beforehand. I mentioned he had written a terrific poem that morning. He fished in his pocket, then proudly read it. Will he have another writing day like this? Will he point to yesterday as the day he swam into the writing current, and decided he wanted to stay there? Did my colleague see this interaction as momentous? An eleven-year-old boy tapped his own creativity, and he knew it. I was giddy.

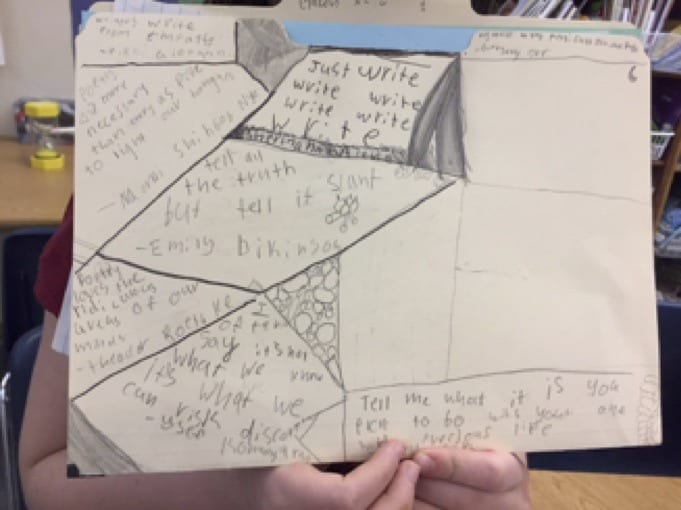

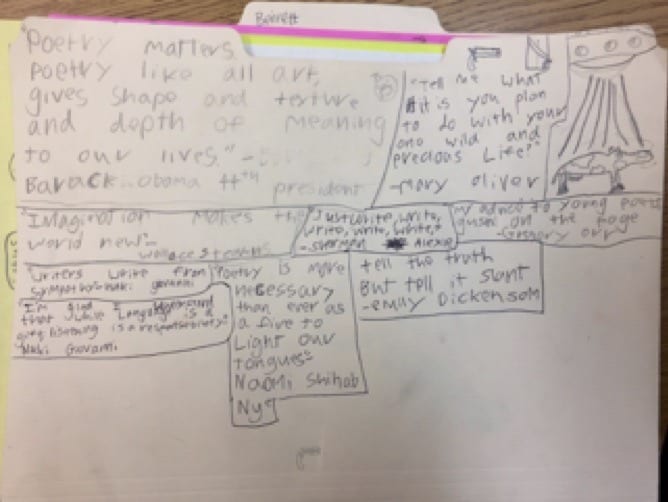

We start every session with a quote from a poet that everyone copies onto their folders. Galen’s folder has great doodled triangles, and space for three more quotes. (We have two more sessions! She’s an optimist, like me!)

And, oh, the poems! The day we read “Knoxville, Tennessee” by seven-time NAACP Image Award winner, force of nature, and poet, Nikki Giovanni, Safiya wrote “My Home,” which is not set in Seattle. Here are stanzas from it:

My heart is where you feel every grain of sand

as you walk to the mosque in the dead of night.My heart is where when you feel the first

rays of sunlight on your face through

your clear glass window and then you hear the

song of the rooster and the hen.

Sure, there are hens in Seattle, but not a barefoot midnight trudge to a mosque. She continues, tying heart to home, and home to Somalia:

My heart is where you always smell

homemade food whenever you come whether

in the dead of night or in the bright of dawn.My heart is where whenever you walk

into any house on the block you see

friends and family just beyond the door.My heart is where my home is

and my home is Somalia.

That same day, Sawyer’s poem, “Satisfaction,” gives us a sonic image that cements our sense that he knows what he’s talking about with football:

I always like

the satisfaction

of scoring

a touchdown.

The dull thud

of the ball in

your hands.

The day we read Salvadoran poet and activist Roque Dalton’s “Like You” credo poem, Barok responded with “Justice.” I include the entire poem, for its wise, hopeful counsel:

Justice

Like you,

I believe that

freedom is for

everyoneLike you I believe that

justice is blindLike you I think that

Black lives matter.Like you I believe

that a mistake is a

lesson.Like you I believe

that injustice is a

possessive power and evildoers

are victims too.Like you I believe that

hate is a wound that can

be healed.Like you I believe

that knowledge

is the key to everything.Like us, we are bound

together like a sentence

connecting.-Barok Gebre

Roque Dalton declares in his final stanza “that my veins do not end in me / but in the unanimous blood.” Barok’s final stanza binds us together “like a sentence / connecting.”

Zander ended his declaration of allegiance to computers, by writing:

We are all connected by programming

or at least by wiring.

Javier Zamora, currently a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, came by himself from El Salvador when he was 14. I was reading Zamora’s Unaccompanied, its epigraphs by Roque Dalton, and his heart-ripping poetic narrative of this journey, as Danielle and I talked about her desire to help her classes build empathy, to learn to see things from another’s point of view.

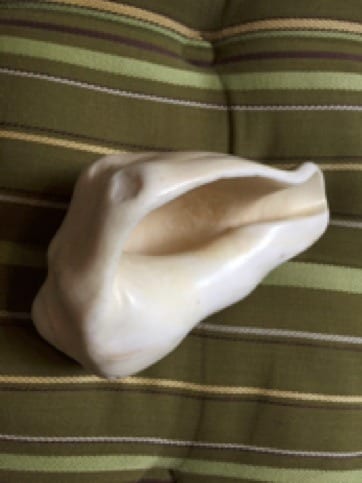

I told the class a bit about Zamora’s story, how his grandmother took over as parent when his mom and dad were disappeared during the Salvadoran Civil War. We read “Abuelita Says Good Bye.” In that poem, Zamora’s grandma gives him a conch shell to remember her by, before letting him leave to try for a new life in the U.S. My dad brought me a conch shell he’d found on Miami Beach when I was eight. I meant to bring it to share along with the poem, but I couldn’t find it.

Kylee said she would bring a conch shell from home, and she did. Our next class, she showed it to us, then blew through it so it called us. For the next few meetings, kids asked me about my shell until the day I was able to tell them I’d found it. I also said my dad died three years ago and that I walked around with it in my hands for an hour.

As I walk down the hall past the office and downslope with right hand view into the library, I look forward to the walls lined with second grade owl drawings. I probably have a few from three years ago somewhere on my phone. Here’s one from last week:

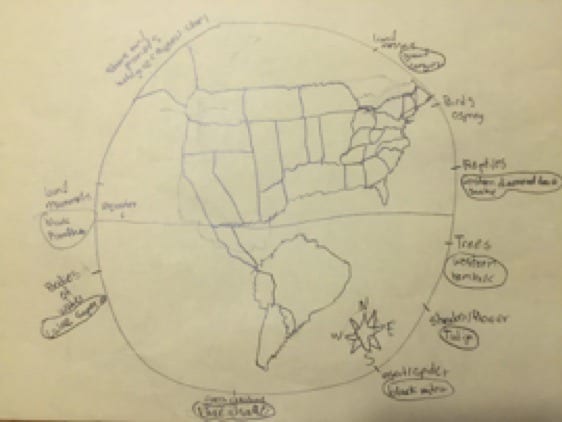

When I read M. Scott Momaday’s “The Delight Song of Tsoai-talee” to the boisterous afternoon group, the room quieted to rapt silence. We drew circles on paper, and wrote the names of animals, plants, bodies of water and other particulars of the natural world around their perimeters in preparation for writing our own “I am” poems. As I talked about how indigenous peoples have seen the world and its beings in circular rather than hierarchical relationship, Edison turned his circle into the earth, complete with compass rose and the Americas (he says the United States are approximated).

Here are some lines from Lydia’s poem, “Life,” that came from that day:

I am the dove at night teaching the wind

to float through her wings.I am the foxglove, poisonous but beautiful,

teaching the animals to admire but not touch.I am the rosebush, teaching that despite its beauty

it can still stab you with its thorns.

Aruni titled her poem, “I Am.” Here is an excerpt:

I am the soft jingle of my aji’s gold bangles.

I am the freshly harvested jasmine

from my auntie’s garden.I am so many things that may not connect

but they are all part of me.

From Hope telling me I “did a great job” my first day in class, to Cash giving me his original poem, “Ten Days to Live,” to Ryan’s constant inspired poetry production, to Josiah worrying about my lost conch, we’ve entered each other’s lives. What we make together are poems, of course, but our work together has sparked a community that has bound 59 of us: teacher, ASL interpreter, WITS poet and students in this sentence we’ve been creating together. As Safiya pointed out, “sentences end,” but that’s why we sing!

Laura Gamache believes reading and writing can save your life. She holds an MFA from the University of Washington, directed their Writers in the Schools MFA Internship Program for 10 years, and has been a WITS writer since 1997. She was a Jack Straw Writers Program fellow in 1999 and 2002, Finishing Line Press published her chapbook, “nothing to hold onto,” and her poems and teaching essays have appeared in many print and on-line journals and anthologies, most recently Sixfold Poetry (Summer 2016). Her band, Feeble Prom Date, is imaginary.

Laura Gamache believes reading and writing can save your life. She holds an MFA from the University of Washington, directed their Writers in the Schools MFA Internship Program for 10 years, and has been a WITS writer since 1997. She was a Jack Straw Writers Program fellow in 1999 and 2002, Finishing Line Press published her chapbook, “nothing to hold onto,” and her poems and teaching essays have appeared in many print and on-line journals and anthologies, most recently Sixfold Poetry (Summer 2016). Her band, Feeble Prom Date, is imaginary.