WITS Voices: Page as Garden

January 28, 2016

By Samar Abulhassan, WITS Writer-in-Residence

“It is like writing my eyes instead of hands.”

“You know how when you go into the wilderness you are expected to bring out your trash, leaving nothing behind? I spent the first half of my life leaving words in the world, and will spend the last half taking them out!” -Mary Ruefle, “On Erasure”

I have been fortunate enough to work in Seattle schools since 2008, exploring poem-making with students of all ages, and have noticed that at the end of a poetry residency, students often recall blackout or erasure poems as one of the most memorable experiments we tried together. Simply stated, an “erasure poem” is the making of a new poem by vanishing the old text that surrounds it.

For this lesson, there is a distinct hum in the room, as this accessible, delightful and surprising way of making a poem is a perfect antidote to any kind of writer’s block. I tell the students about erasure poet extraordinaire Mary Ruefle, how she has likened a page full of existing text to a field of flowers. Your goal is to meander the fields, and choose what you like, I tell them. (I find it is actually important to encourage them to NOT read the text carefully, to work quickly and enjoy stumbling, trusting pre-cognitive leaps.) What will you choose to keep and what will you leave out? For both my students at the Hutch School and Port Townsend’s Blue Heron School last fall, this invitation induced a trance of sudden, electric connections, loosening all of us from our usual vocabularies and the sometimes arduous task of pulling words from the ethers.

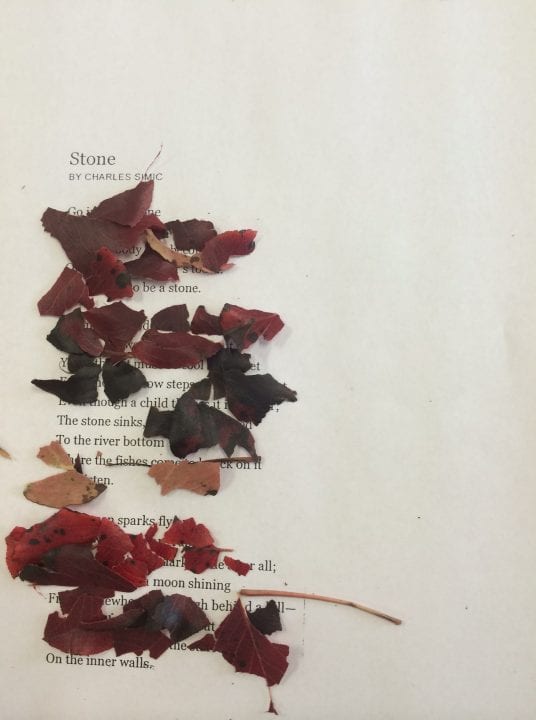

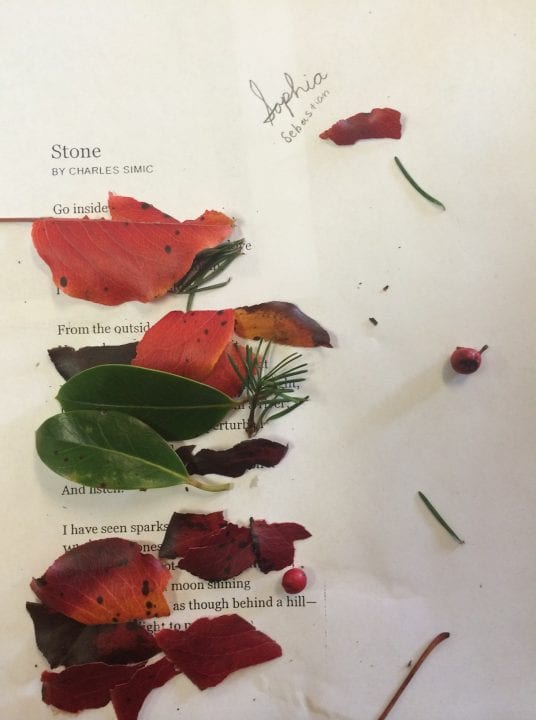

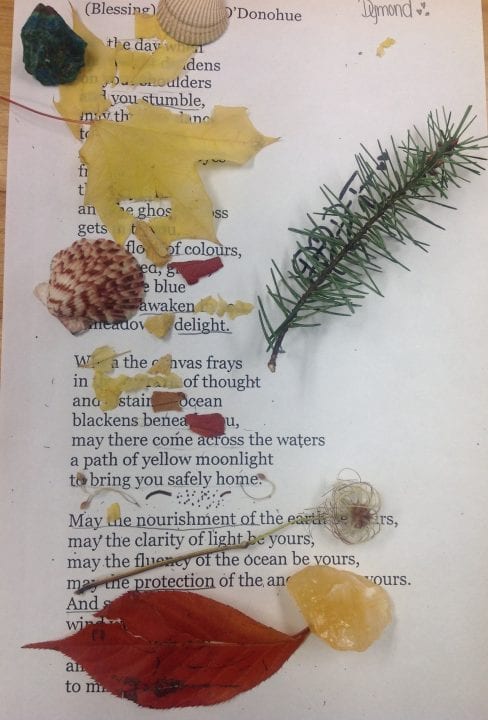

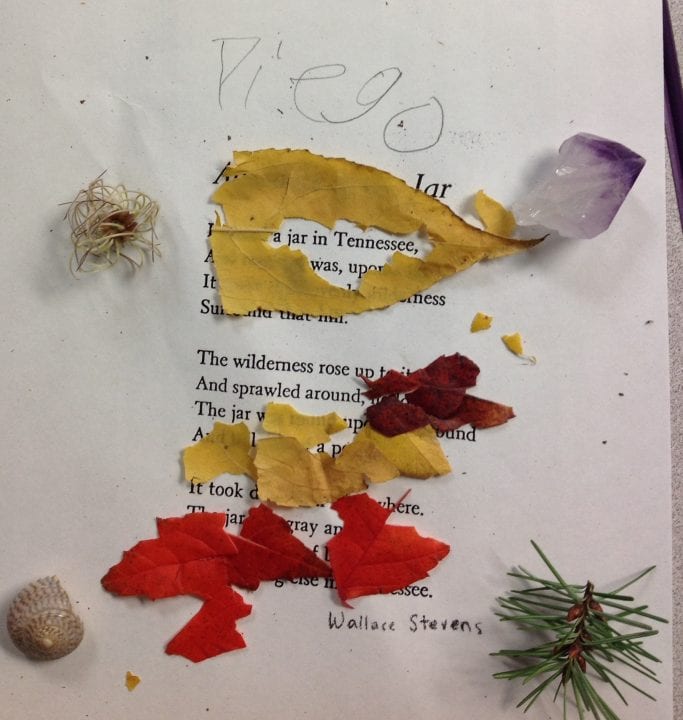

This past fall I caught glimpse of lesson notes from poet and teacher Jessica Smith, who tried “wilderness erasures” with her high school students in an experimental literature class. I loved this version of altering texts, and happen to love autumnal colors, moods and textures, so I couldn’t pass up a chance to merge poetry and the infinite leaf shades of orange-reds and burgundy-blacks. To plan for this lesson, I gathered fallen leaves and acorns, rosemary sprigs and rocks. Rather than hand out a set of black markers, or gather endless bottles of white-out, I offered students a smattering of plant life on their desks. Their mission? To use the objects to obscure text, choosing what to reveal and what to hide. I told them to work intuitively, and to experiment with numerous combinations, to feel free to break the rules of grammar in favor of sonic freedom and mysterious combinations. When using white-out or black marker, it’s hard to undo a creative decision; this method keeps it relaxed while highlighting spacious possibility and surface. Finally, at class end, I offered to take a picture, and their arms instinctually circled their ephemeral poems in a protective stance. It was a good moment to talk about the joy of making something and letting it go.

Like white-outs, wilderness erasures reveal texture, beauty and loss. A torn leaf becomes window frame to one word, while eclipsing others. Curled leaves might mimic punctuation marks: a red berry dots the word “hill,” a vein of a shriveled red-brown leaf underlines the word “bare,” a loosened stem draws a vertical path and steers the eyes in a fresh direction. The ghosts of words, or parts of words, linger. “Things are starting to get really weird,” said one middle school student at the Hutch, as I emptied the friendly foliage from my paper bag on his desk. He went to work carefully tearing leaves to highlight fragments of lines.

An “art walk” at class end is a terrific, quiet way to share work. Even though in this case all students were working on altering the same poem, their choices were varied and point to our wildly diverse temperaments. And in Port Townsend, where I last offered this lesson, I reminded students of the used bookstore downtown that often offered “free books” in a cardboard box outside the store. A vintage text on automobiles or medical encyclopedia are often the best kind to alter. Still, I don’t think this method is for everyone, but I do think it is worth knowing about.

For my own private journey, making a set of new erasure poems last year freed me of a longtime impasse of feeling bored with my usual thought patterns. The poet Matthea Harvey was in town and invited us to play with erasure during a workshop for Seattle Arts & Lectures. Homebound for several days in a row with a few bottles of white out and xeroxed text, I felt a welcome glee and supple support, which brought me in close conversation to something potent, long dormant. It also brought back a time in childhood when I had just learned to read and was discovering the beauty of street signs and billboards, or words etched on sidewalk, and was taken with how words became ravaged by weather and paint and decay. This simple lesson refreshes our interactions with the world — it’s as if each word is restored to its vibrant and vulnerable state.

Samar Abulhassan holds an M.F.A. from Colorado State University and worked in California public schools for seven years. Born to Lebanese immigrants and raised with multiple languages, she is a 2006 Hedgebrook alum and the author of two chapbooks, Farah and Nocturnal Temple.