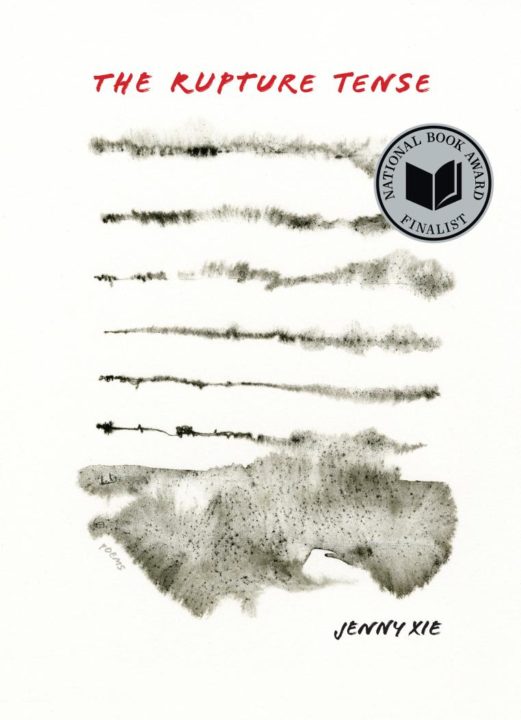

An Intimate Provocation: Jenny Xie’s “The Rupture Tense”

January 16, 2023

This essay is part of a series in which Seattle Arts & Lectures partners with Poetry Northwest to present reflections on visiting writers from the SAL Poetry Series. On Tuesday, January 17, Jenny Xie will read and discuss her work in conversation with Jane Wong at Rainier Arts Center, at 7:30 pm (PT). Tickets to this in-person and online event can be purchased here.

By CMarie Fuhrman

“If there is an afterlife,” Jenny Xie writes in “The Rupture Tense,” the title poem of her newest collection, “she’s borrowing language from it.” I found this line as if overheard in a conversation. I was sitting on a ledge, New Year’s Eve, southwestern Utah, my back against a wall, Xie’s book as my companion. I had come to this place, as I do every year, to reflect. I had just left my mother’s house in Colorado, where I spent hours looking through old photographs—another of my traditions—and sharing stories while creating new ones. I see my family only once or twice a year, so the stories hold more importance, as if they are grains of self I am taking with me, a way to know who I am. All of us who have survived gathered in my sister’s living room; there are no more than a dozen of us now. Soon, the photographs will take the place of the eldest, and eventually, me.

Above me, an ancient hand is pecked into the sandstone wall. Another picture, though this one is now considered art, as if to raise its value. Could the artist ever have known that thousands of years later, one of their descendants would spend days considering that single hand’s meaning? I want to believe they must, for why else do we leave messages? Why else do we make art but to communicate our presence with the future? I have brought along Jenny Xie’s book as my companion for this questioning. Written in an intimate voice that engages the reader in her own reckoning, The Rupture Tense is perfect for a cultural, familial, and self-understanding journey.

The first section, “Controlled Exposure,” examines cultural and artistic lineage. How what is found (like the handprint above me) reminds of what is lost. The poems in this section are written in response to the poet’s encounters with some of the nearly 100,000 black-and-white photographs made by Li Zhensheng during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Here, Xie examines loss, location, and her cultural lineage. The stanzas, often created as lists or slideshows, read like an inventory of people, places, and things organized around identity. In “Memory Soldier,” a poem that marches forward with declarative lines and sensuous images, Xie writes, “Yet the distance between the seen and the known can’t be crossed by the senses.” Of the photographs, and almost in contradiction, she writes of the people in the images. “The hanged. The lashed. The suicides. The betrayed. The paranoid. The disappeared. The executed, slender backs to the firing squad.” The simplicity of merely stating what is, without description, evokes a sense of wonder. A sense of failure. The weight of which becomes felt. The images pile in the reader’s mind as they would have beneath the floorboards of Zhensheng’s home where they were hidden. They evoke a sense of loss through what is found. In the reflective voice of the speaker, and later in the poem, “A photograph is no place to keep the dead.”