The Seattle Children’s Broadsides Project with Sierra Nelson, Ann Teplick, Jenny Wilkson

December 10, 2020

By Gabriela Denise Frank

During our conversation about the Seattle Children’s broadsides project, WITS writer Sierra Nelson raised a familiar inner doubt.

“As a writer and an artist, I wonder, what is it for?” she said. “Like, what good does art do? Sometimes, it does so little. I wish it could change everything—or change something.”

Sierra was speaking to the Why, as in, why does one make art? Inferred in the Why is the Who, the What, the How—Who cares, ultimately? What’s the point? How does one person’s art matter to the world, especially in times of crisis? Some artists grapple with these questions at critical junctures while others face them regularly, even daily, in their creative lives.

We came to this crux after I asked Sierra and her partner-in-poems, WITS writer Ann Teplick, and Jenny Wilkson, former Director of the Letterpress Program at the School of Visual Concepts, to describe how this project has affected them as artists and humans. For all three, the answer came down to Why.

First—a little context.

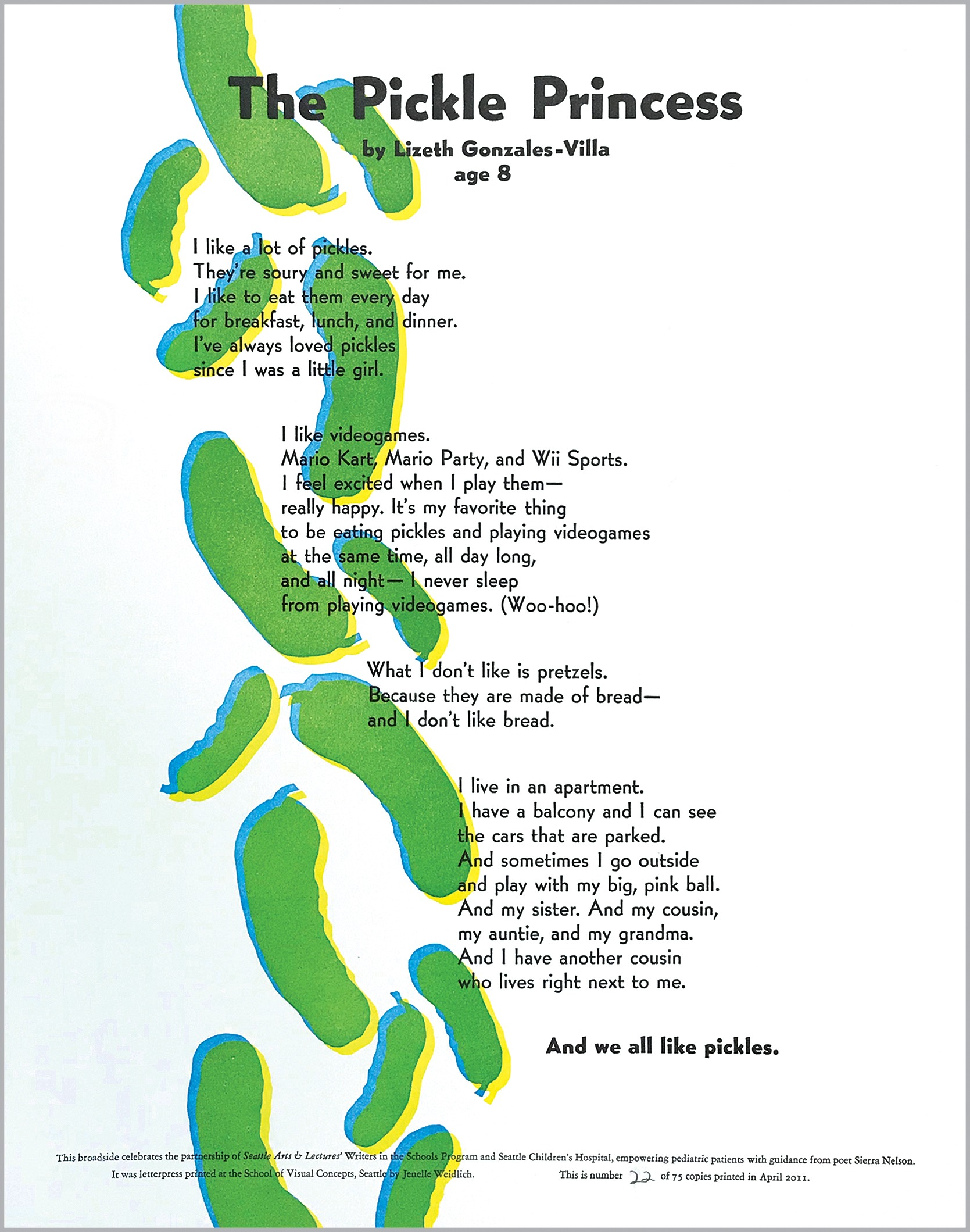

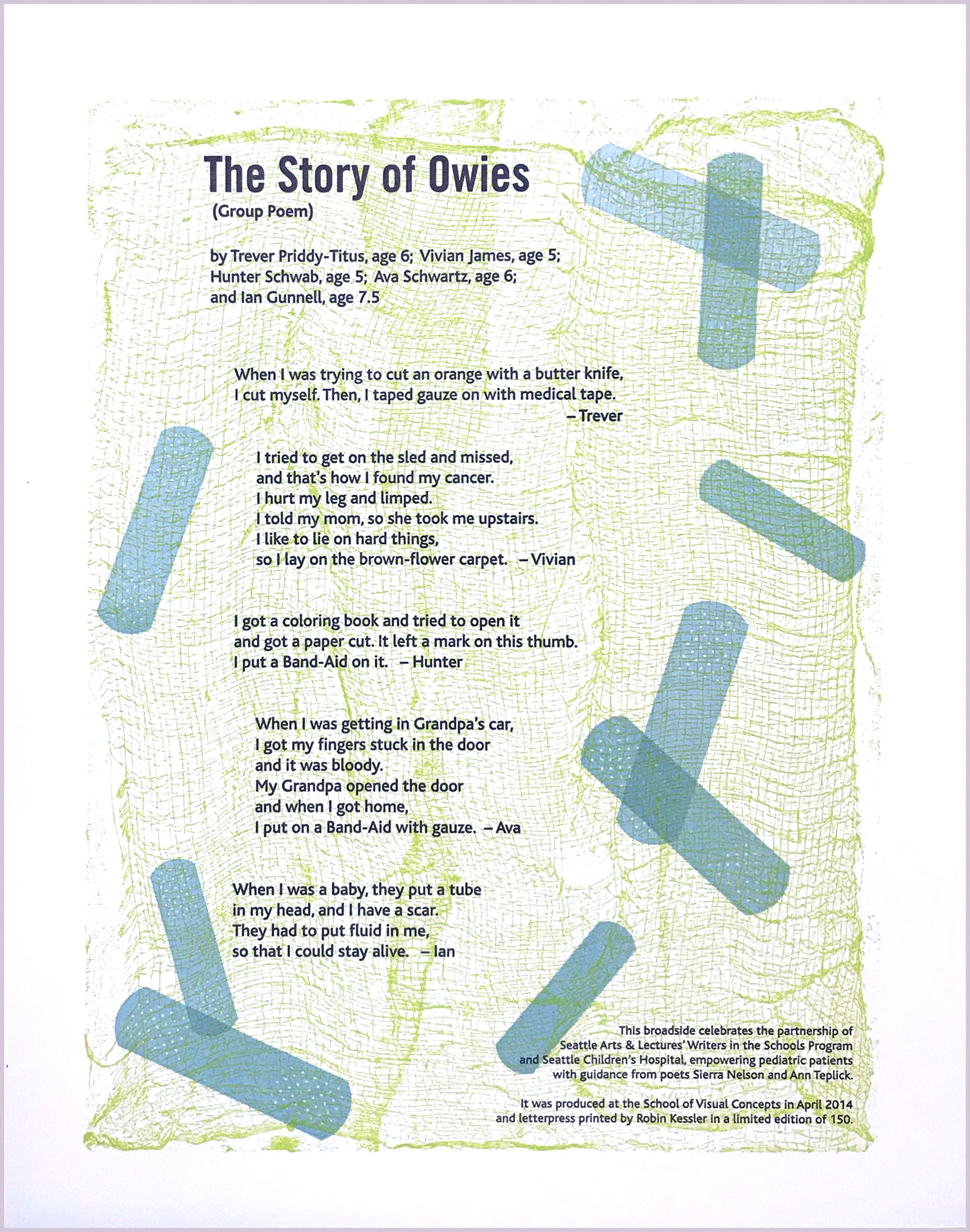

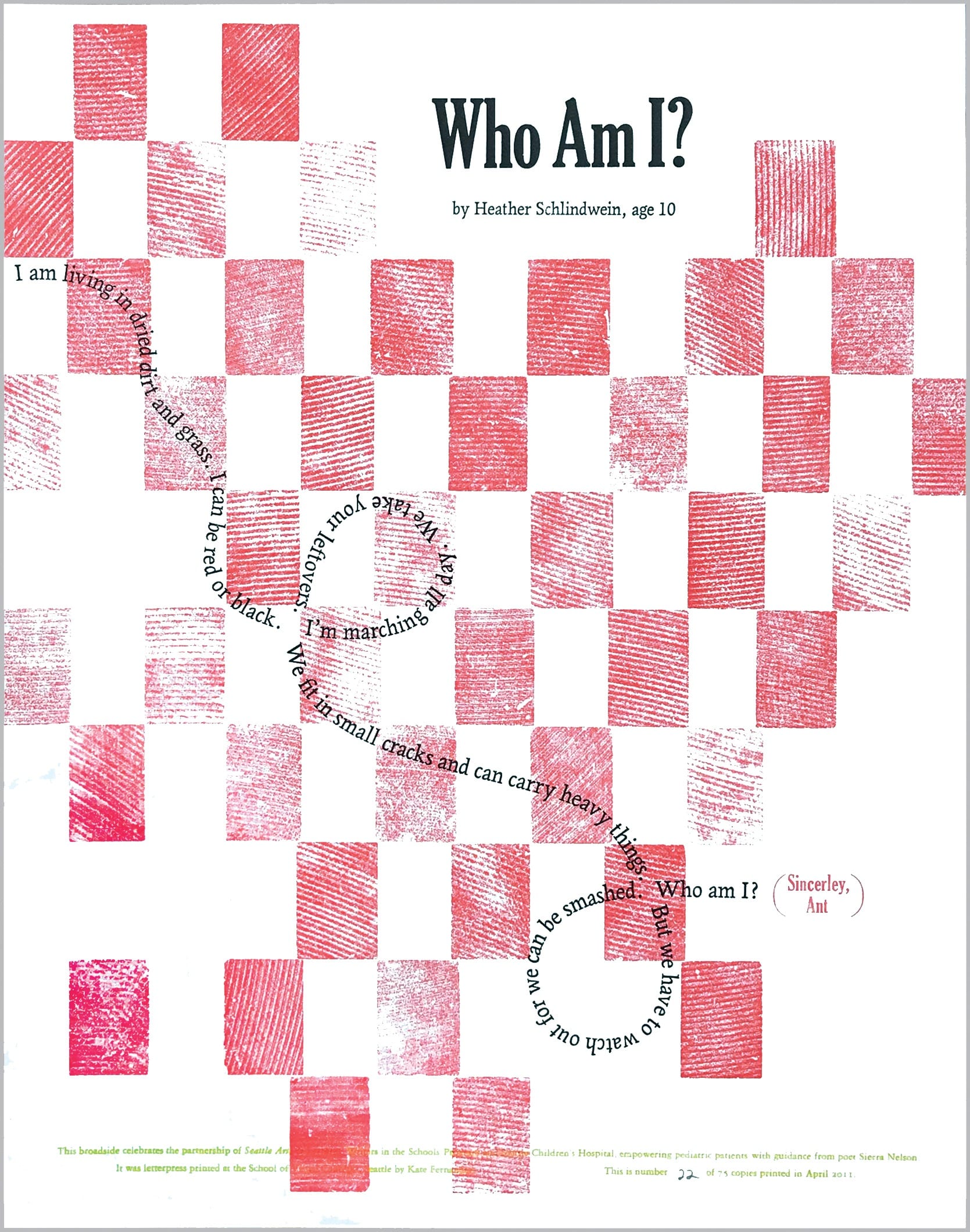

For the past ten years, these women have collaborated with youth poets and letterpress artists to create an annual compendium of custom-printed broadside poems. These portfolios are meticulously crafted and gorgeous in every way. The project began with a spark from Sierra who was mentoring young writers in treatment at Seattle Children’s Hospital. She often typed up their poems and printed them from her desktop printer.

After she saw how meaningful it was to the students and their families to have a physical copy of their poems to pin up in their rooms, Sierra dreamed of delivering letterpress versions. She reached out to people in the letterpress world, some of whom she had never met, asking whether they would be interested in partnering with her students. This is how she connected with Jenny at School of Visual Concepts. With support from SVC’s co-director, Linda Hunt, Jenny’s vision helped the project blossom from individual broadsides into a commemorative cloth-bound art object that encompasses the work of twenty-some poets matched with letterpress artists each year.

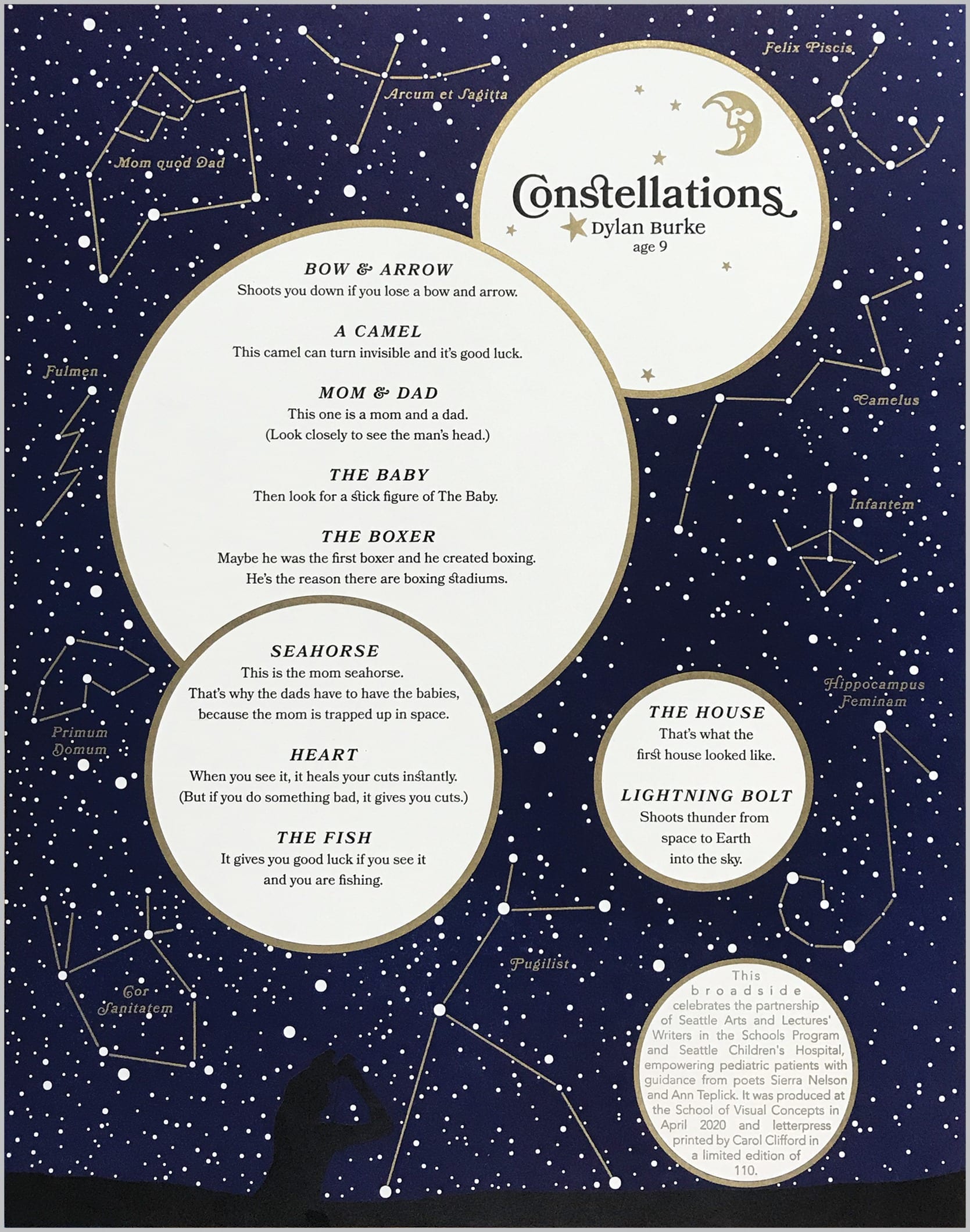

The broadside poems are written by youth, ages four to twenty-four, who work with Sierra and Ann one-on-one and in small groups. Each winter, Ann and Sierra select a handful of poems to be illustrated and printed pro-bono by letterpress artists affiliated with the School of Visual Concepts. SVC donates resources alongside generous in-kind donors who contribute book cloth, paper, and photopolymer plates to print the broadsides. The portfolios are presented to the poets and their families at a celebration event that includes a reading.

The process is emotional for everyone.

“To see a young writer write toward their experience, even if it is heartbreaking or scary or devastating—to have become a creator in that moment—to take that experience and express it does shift things,” Sierra said. “It doesn’t change anything that’s happened, but it does create space where they’re able to sense relief and connection.”

“To see a young writer write toward their experience, even if it is heartbreaking or scary or devastating—to have become a creator in that moment—to take that experience and express it does shift things.”

Ann agreed. “This work has made me a stronger person, a more compassionate person. It’s helped me to be more of an improvisational artist, doing it as we do it, changing it up at the last second, and not being afraid to do so. Meeting students where they are, and they are at different places, physically, mentally, and emotionally. It’s helped to strengthen my mindfulness practice. Being present in the moment with all that presents itself. And listening on a deep and focused level.”

Jenny noted that the Why of the broadsides project is the sense of doing good. “It’s reinforced that, to find a place for letterpress printing in our community, you have to make sure the projects are meaningful. This was the perfect project where something tangible and valuable needed to be created for these poems to last, to build legacy for these children.”

It’s interesting how, when one’s art emerges under the mantle of service, the urgent yearning to define Why eases. Why becomes about helping another human tell their story. It isn’t about publication or glory; it doesn’t aggrandize individual talent. Instead, it creates community, which is what people turn to in times of crisis. Why becomes about listening rather than telling, about connecting, about offering one’s gifts to aid strangers—about facing something together through art that would be terrifying to face alone.

A teenaged poet said to Ann, “Poetry helps me to get things out of my heart.” Another told her that writing helps him figure out the real person he is inside, and who and how he wants to be in the world as this person. Another hoped that those who read her poem will understand the challenges she faces every day, invisible to everyone except she and her family.

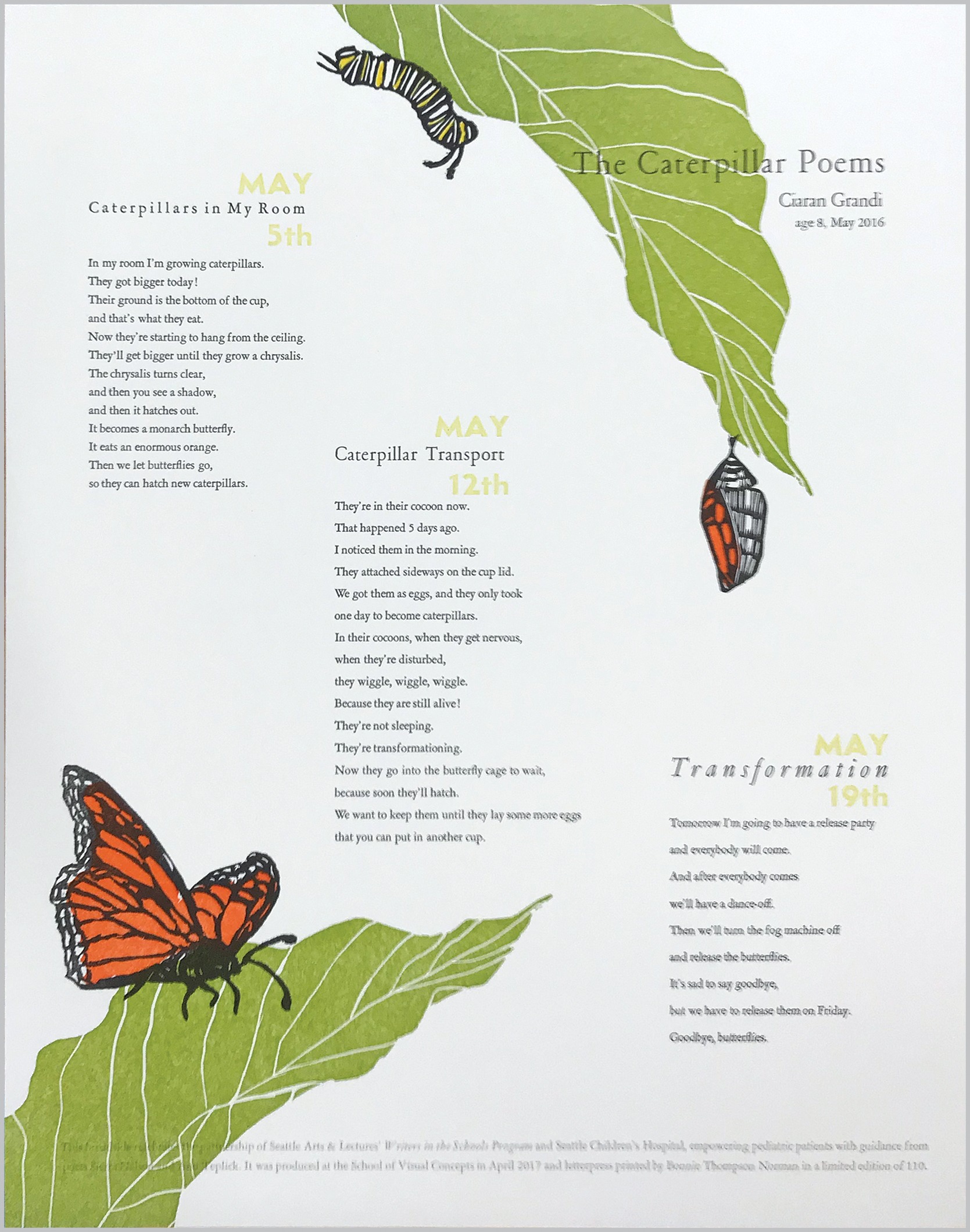

Sierra shared her experience working with an eight-year-old poet who wrote a series of poems about caterpillars, which he watched hatch in a jar in his hospital room.

We got them as eggs, and they only took

one day to become caterpillars.

In their cocoons, when they get nervous,

when they’re disturbed,

they wiggle, wiggle, wiggle.

Because they are still alive!

They’re not sleeping.

They’re transformationing.

His last poem imagined a celebration in which guests would participate in:

a dance-off.

Then we’ll turn the fog machine off

and release the butterflies.

It’s sad to say goodbye,

but we have to release them on Friday.

Goodbye, butterflies.

His poems are sweet and enchanting, but it was the tenderness with which Sierra described her surprise—the butterfly dance party really did happen!—that left me misty-eyed. It was nothing short of magic: an eight-year-old’s dream was transformationed into reality through the alchemy of poems.

“Sometimes, that is the miracle that occurs,” Sierra said. “It can be just as powerful, or another kind of power, to use your imagination. You create space for physical relief, to be outside of your body and pain for a moment, a space that others can enter. That has renewed my faith in what writing can be.”

“It can be just as powerful, or another kind of power, to use your imagination. You create space for physical relief, to be outside of your body and pain for a moment, a space that others can enter. That has renewed my faith in what writing can be.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and flow.

Gabriela Frank: Congratulations to all three of you on a decade of meaningful, beautiful collaboration between Seattle Arts & Lectures, School of Visual Concepts, and Seattle Children’s Hospital. I’m curious, how did you come together around the broadsides project?

Sierra Nelson: It started my second year at Seattle Children’s. I was working with students who were writing amazing poems, and often I was scribing or working with them on the page, then typing up their work and bringing it to them from a printer. I saw how much it meant to have their work to put up in their room, to have their voices reflected back, how meaningful it was, that very small gesture even on a low-fi scale.

I worked with some students for weeks or even months. Some students were struggling with their health or their path was getting more difficult, and they had a lot of questions about their health. I saw how meaningful it would be for the families to have something beyond a piece of paper, that we could do something more in legacy building. I had been thinking it would be amazing to have a letterpress. It wasn’t a skill I had, but I knew people in the community who were doing it, so I emailed folks I knew, some of whom I hadn’t met before, and asked if they would be interested in working with students. A couple of people had thoughts, including Linda [Hunt, co-director of the School of Visual Concepts] and Jenny.

Jenny Wilkson: The three of us met in person at the School of Visual Concepts. Sierra brought a stack of poems and—we really need to give credit to Linda Hunt here—Linda said, “Yes, we want to donate our resources to publish these poems.” After Linda gave the go-ahead, I reached out into our larger letterpress community and found enough printers to make the project happen that first year.

Sierra: It was really thanks to your vision, Jenny, and Linda’s go-ahead that it became a project that was able to continue. You expanded the scale beyond what I imagined. I wanted these poems to be honored in some way, and you had the vision to make a portfolio of them. You were like, “What if we bring together this community of letterpress artists so they’re not working solo, creating a small stack for only that family—what if the families would be honored and have these beautiful letterpress projects and get to experience all the poems? What if that set could be appreciated and celebrated in the community?” Opening that door to these larger possibilities was even dreamier and more amazing.

Jenny: I remember, for you, it was about the families. You wanted to get this done for the families. Then, because we were printing so many, it was like, well, why not make this a portfolio that can serve all of the organizations as donor gifts?

Gabriela: Ann, were you involved at this point?

Ann Teplick: No. I began my residencies at Children’s in 2011 and joined the letterpress project then. I

Gabriela: How does the program work?

Ann: Each week, before COVID, I began with an hour in the one-room classroom where I wrote with small groups of students, ages 6-18. I moved then to an hour in the Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine Unit (PBMU), for another group writing session. During my third hour, I wrote 1:1 with students in their hospital rooms. I’ve also worked with students at Ronald McDonald House. The residency starts up in September and wraps up in late May or early June. Most of the letterpress poems come from the poets we’ve written with during our current residency. Some come from the previous one.

Sierra: It’s kind of similar to other residencies in that we’re usually going in once a week, when we were going in, that is. Sometimes we’re working with elementary kids, or kids who are a little bit older in the classroom, but it can vary. It’s a one-room classroom and they could be any age.

Ann: They call it the healthy classroom—you need to be not sick to walk in the door. I usually spend an hour there, an hour in the Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine Unit (PBMU), then my third hour is floating around working with people individually.

Sierra: I float around almost entirely. I will occasionally work in a small group, but I’m almost entirely working one-on-one with students who may be undergoing treatment where they have to be in their room, or they’re more based in their room. Most of my referrals are through the palliative care program.

When we’re looking at poems that might be selected for letterpress, Ann and I are looking across all the student poems that we have permission to publish, choosing ones we think would be meaningful for students—and short enough. Only so much can fit on the page, so that’s also a consideration.

Ann: Sierra; Alicia Craven, [SAL Director of Education], and I meet in February to choose the poems. Before we meet, Sierra and I send ten to fifteen poems each for the three of us to consider. The editions contain approximately twenty poems and we try to keep it evenly divided. When decisions are made—and it’s never easy—we send them to Jenny to send to the participating artists, whom we meet in the spring to read the poems aloud and to share anecdotes and process. As well, to see which artist would like to work with which poem. Over the years, this choosing has evolved in an organic way. Currently, we use stickies on the wall (Hail to the Stickies! We cheered when this idea was suggested) that reflect the artists’ choices. We meet up again with the artists in May, to celebrate their work, and to hear the stories of their process. Sometimes, the artists make connections with the poets through phone calls and/or visits to the hospital to share their vision for the art, and to better understand the poet and the poem created. This project celebrates joy, hope, inspiration and legacy.

Gabriela: Jenny, how does the letterpress process work after the artists select the poems they want to illustrate?

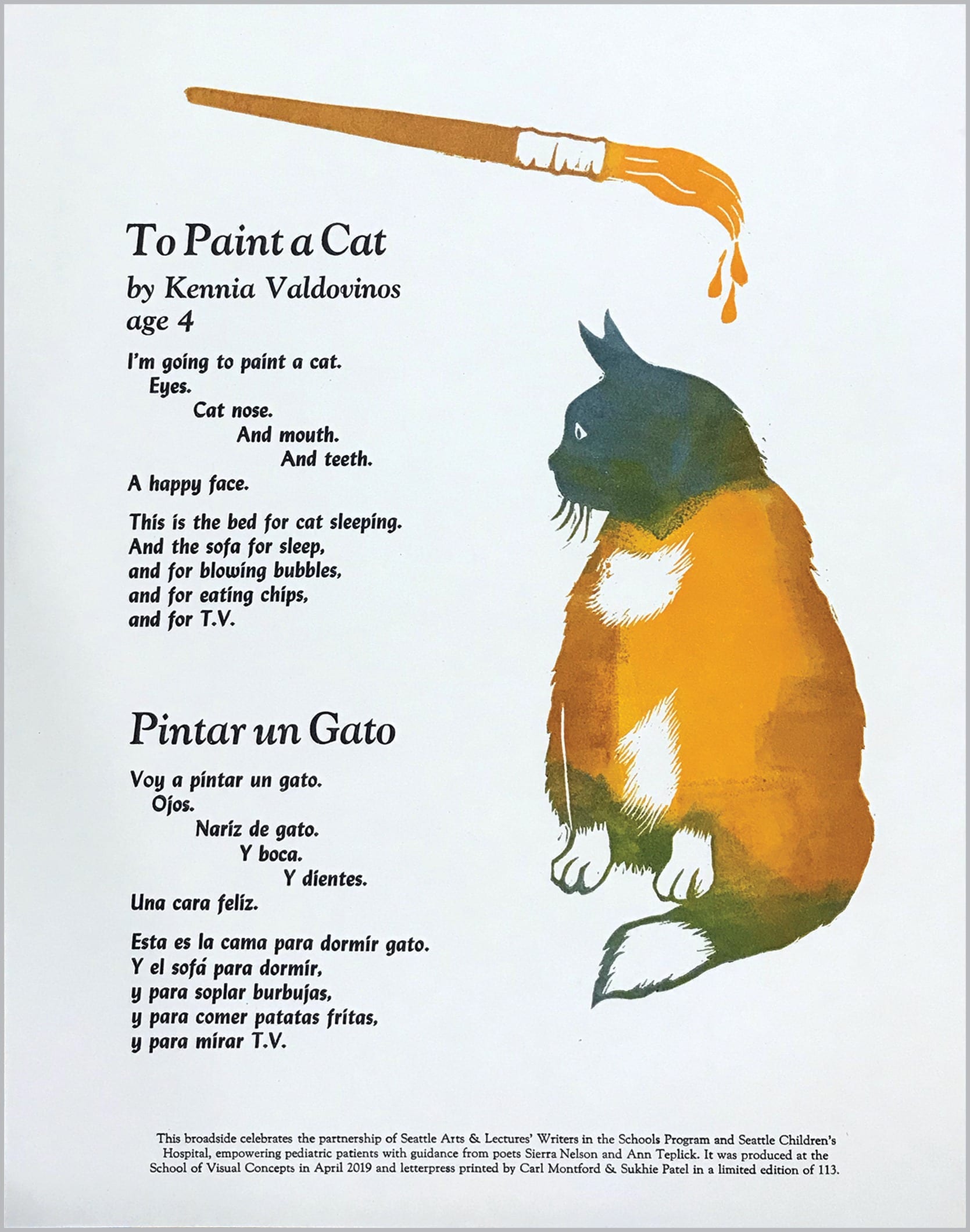

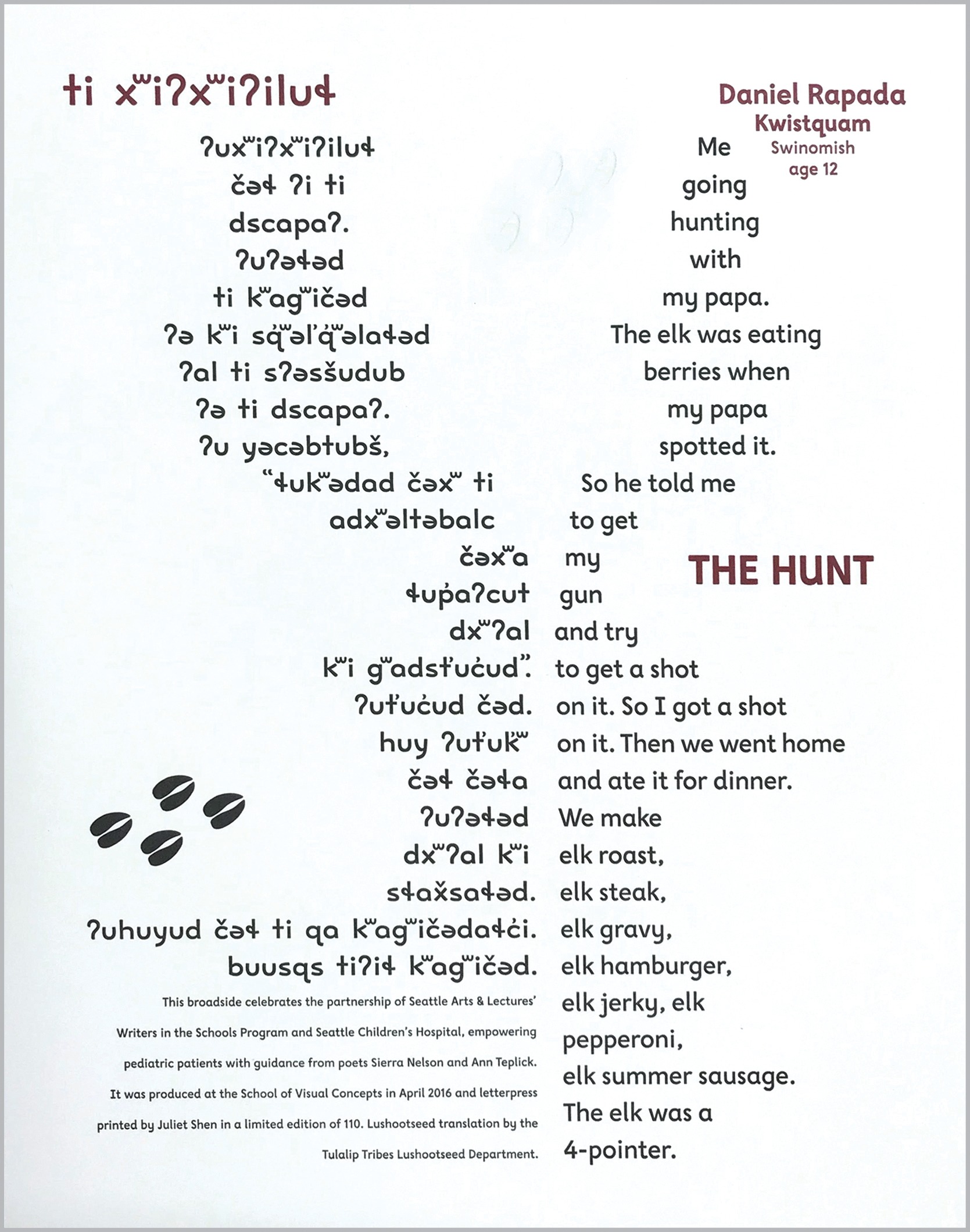

Jenny: As Ann said, we fight over the poems in March [laughs]… Each letterpress artist works in various ways. Some enjoy setting type by hand. They might choose shorter poems or poems that are within the limitations of the materials they like to work with. Other artists enjoy designing digitally, so they might go for poems that have translations and accents and things that wouldn’t be easy to do if they were setting the poem one letter at a time.

There are so many possibilities in letterpress printing as an art form. It’s been fascinating to see these artists approach it in an experimental way. A lot of the illustrations you see in the portfolios use unconventional techniques. Some people are using objects and raising them to the right height for printing and creating printing plates out of them; we’ve had people print from bandages, for instance. Since they’re doing it pro-bono, the artists use this opportunity to give themselves creative freedom to try a technique or do something fun that they might not have permission to do otherwise. It’s been really cool every year to learn from the other printers about the experimental techniques they’re using to create illustrations for the poems.

Gabriela: You do a lovely job of breaking down the storytelling behind the design of the broadsides, by the way. The story of Gerald the Llama posted online was brilliant, and I loved seeing the different graphic approaches to the Hulk.

Jenny: Yes! The artists are using not only metal type but the backside of wood type—they’re using Legos, hand-carved linoleum, and pressure printing, where they’re actually using built-up layers of paper to impart different shadings of ink transfer—just really cool stuff that makes it interesting.

Gabriela: How has the program changed over the years?

Jenny: It would be great to note how it is not changed. All of our in-kind donors have stuck around for ten years, which is remarkable. From the book cloth from Ecological Fibers to the paper from Neenah to the photopolymer plate donations from Boxcar Press, all of the companies we reached out to for our first portfolio have said yes year after year to make this happen. I’d love to give a shout out to those in-kind donors.

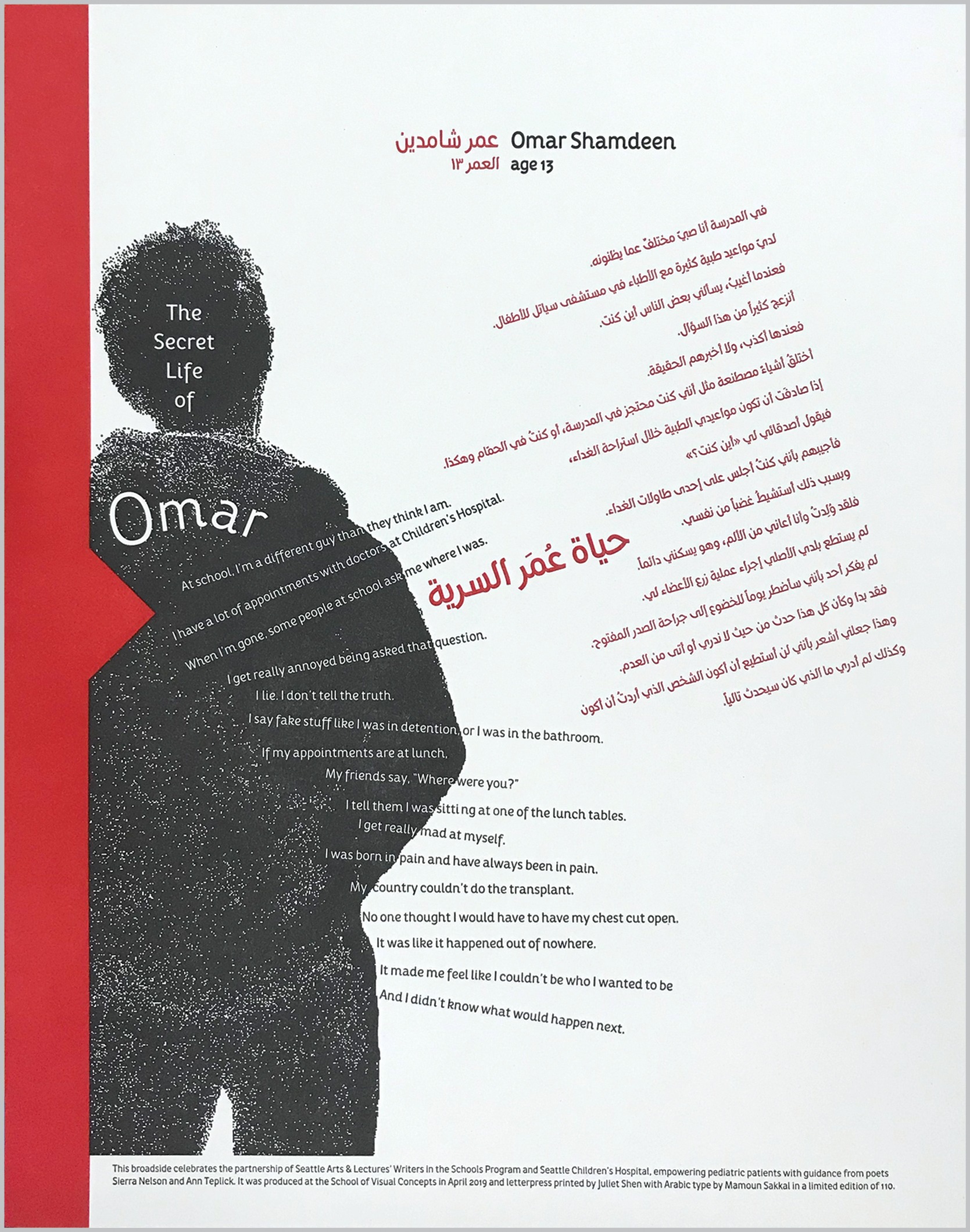

The way it’s changed is that we’ve done more and more translations. Now, at least half the poems have a Spanish component. We’ve done two Arabic poems. We did a Lushootseed translation. The fact that we have a letterpress printer, Juliet Shen, who designed a typeface to print Lushootseed is pretty remarkable. Then, this past year, we were given the opportunity to do a Braille translation. The communities we’re serving are broadening every year.

Sierra: I will add that, each year, a couple of letterpress artists are doing the project for the first time, which is cool. There are a few who have done it every time, and some folks come in and out as they are able. I’ve noticed that artists will work in teams to help with the design or the printing. It’s so beautiful to see that community continue and hear stories of how people helped each other in the printing process. That community has continued to show up for the project and to deepen their connections with one another.

Ann: I’ve noticed many of the letterpress artists gravitate toward the same kind of poems each year. Some lean into the heavier, and some take on the more playful.

Jenny: Our letterpress community has grown right along with the Seattle Children’s broadside collaboration. This has been the grounding project that keeps our community together. Even if we haven’t seen certain people in months, the fact that Children’s Hospital is coming up guarantees we’re all going to be together in the same room again, working for a common cause. It’s been the glue for the last ten years that’s held us together. I’m so grateful for that.

It’s been even more meaningful, as we’ve lost our space this year, to have this project grounding us. Having it be something we can work toward when everything else was taken away from us due to the pandemic was incredibly important this year, above all other years. The fact that we could pull it off without our space and rely on the kindness of other printers printing it in everybody’s studios not only galvanized our community, it proved to us that there is a future for our community beyond the physical walls of the School of Visual Concepts. In the fall of 2020, we reinvented ourselves as a new organization, Partners in Print, so that this important work can continue.

“The fact that we could pull it off without our space and rely on the kindness of other printers printing it in everybody’s studios not only galvanized our community, it proved to us that there is a future for our community beyond the physical walls of the School of Visual Concepts. In the fall of 2020, we reinvented ourselves as a new organization, Partners in Print, so that this important work can continue.”

Gabriela: Are the letterpress artists also teachers?

Jenny: A good portion of them are. They’re teachers, teaching assistants, and super-advanced students. The prerequisite for printing was that you needed to be signed off on the equipment, which takes like a few years of skill.

Gabriela: Can you share some memorable experiences? What has stuck with you in working with the kids, their poems, and the letterpress artists over the years?

Ann: I worked with a young man from Iraq. He’s fourteen now. He wrote a beautiful poem that was translated, in last year’s edition. And he wrote the introduction for this year’s edition. When I first met him, he was just trying to understand the medical spiral he faced, and why him. He was twelve then, and angry about being in the hospital. One of the first things he said to me was, “Even if you read a book about my life, you wouldn’t know who I am.” I wrote that down. It was the focus of our two years working together.

“He was angry about being in the hospital and one of the first things he said to me was, ‘Even if you read a book about my life, you wouldn’t know who I am.’ I wrote that down. It was the focus of our two years writing together.”

I had the opportunity to meet his family. His mom accompanied him to the hospital classroom, and we developed a warm and witty rapport. She cooked a delicious Iraqi meal for the Education Department. This poet was the last student I saw before COVID, when we met to craft his introduction to the 2020 letterpress edition. He said, “I want to get this right. I want to get my story out there. I need to. I want to let other people know that you can do this.” I’m grateful to have worked with him, and for his courage to be a truth-teller.

Jenny: Sierra, tell the story about the butterflies. Is that too sad?

Sierra: It is sad. But it’s such a sweet one. So, the student that both Ann and I had the opportunity to work with, he really wanted to have caterpillars in his room. I think they had to bend some rules to get that okayed—you’re not supposed to bring in flowers or anything like that—although the nurses and doctors knew there was a caterpillar in the corner, this little container of eggs to caterpillars. Each time I would go in, we would write a new poem about what was happening with those caterpillars, so it became a series of poems about the caterpillar release.

The last poem we worked on was about what their release into the world was going to be like. It seemed kind of a fantastical vision of this party where there was going to be dancing, and it was going to be an over-the-top party. But he was able to have that party! I got to go to the butterfly release party and everyone danced. The doctors and nurses and everyone who had worked with him had the chance to see these butterflies released and it was very beautiful—and, amazing. There were these poems about that, and it really did happen. It was his wish to have that, and then he passed away. I’m so thankful to have those poems as this beautiful broadside that celebrates that very special span of time where so much was happening for him medically, and things were really intense. These caterpillars were touchstones of hope and wonder.

Jenny: Sierra and Ann are both are so good at finding these poems, and helping the children write poems that on the surface aren’t about their hospital experience. But, you know, adults reading them clearly can see it’s a metaphor for their hospital experience. There’s so many like that, that are so incredibly touching.

Gabriela: Thank you for that, and for the work that you do. I’m curious, what does this program look like going forward at Seattle Children’s?

Ann: I’m currently teaching on Zoom, one-on-one. The classrooms shut down in March. The teachers work from home, as well as come into the hospital. I’m recording, with the teacher in the Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine Unit, lessons in fifteen-minute bites. I miss being with everyone in person. But I’m thankful for videoconferencing. We need poetry more than ever, now.

Sierra: I’m also not going in. I’m thinking forward to when, eventually, things shift and when it would be possible to come in. We’re trying to set up WebEx appointments with students and find other ways to connect virtually.

Gabriela: How do you, as WITS writers, collaborate with classroom teachers at Seattle Children’s?

Ann: In the past, I’d create a syllabus for the teachers before we began the residency. It changed many times before I walked into the classroom. Often, on the drive to the hospital or when I had a sense of the students at the writing circle that day. A teacher or two always joined me at the circle and wrote and shared their work with the group. For many years, I collaborated monthly with the art therapist. We’d choose a theme; I’d bring a mentor text that spoke to that theme; and she, an art activity that reflected the mentor text. There’s been quite a few poems in the letterpress project inspired by this collaboration. Sierra and I and the departments we work with celebrate National Poetry Month in April with posters on the wall that contain prompts for anyone passing by to fill in. “These are the words I need to hear…” “My superpower is…” “If my heart could speak it would say…” are a few of the many prompts we’ve used. At the end of the month, we have a poetry celebration at the hospital with current and former students, teachers, families, anyone who would like to join us and read a poem they’ve written, or one they love. It’s another highpoint of the year.

Gabriela: Jenny, do you get to hear the kids’ reactions to their poems printed as broadsides?

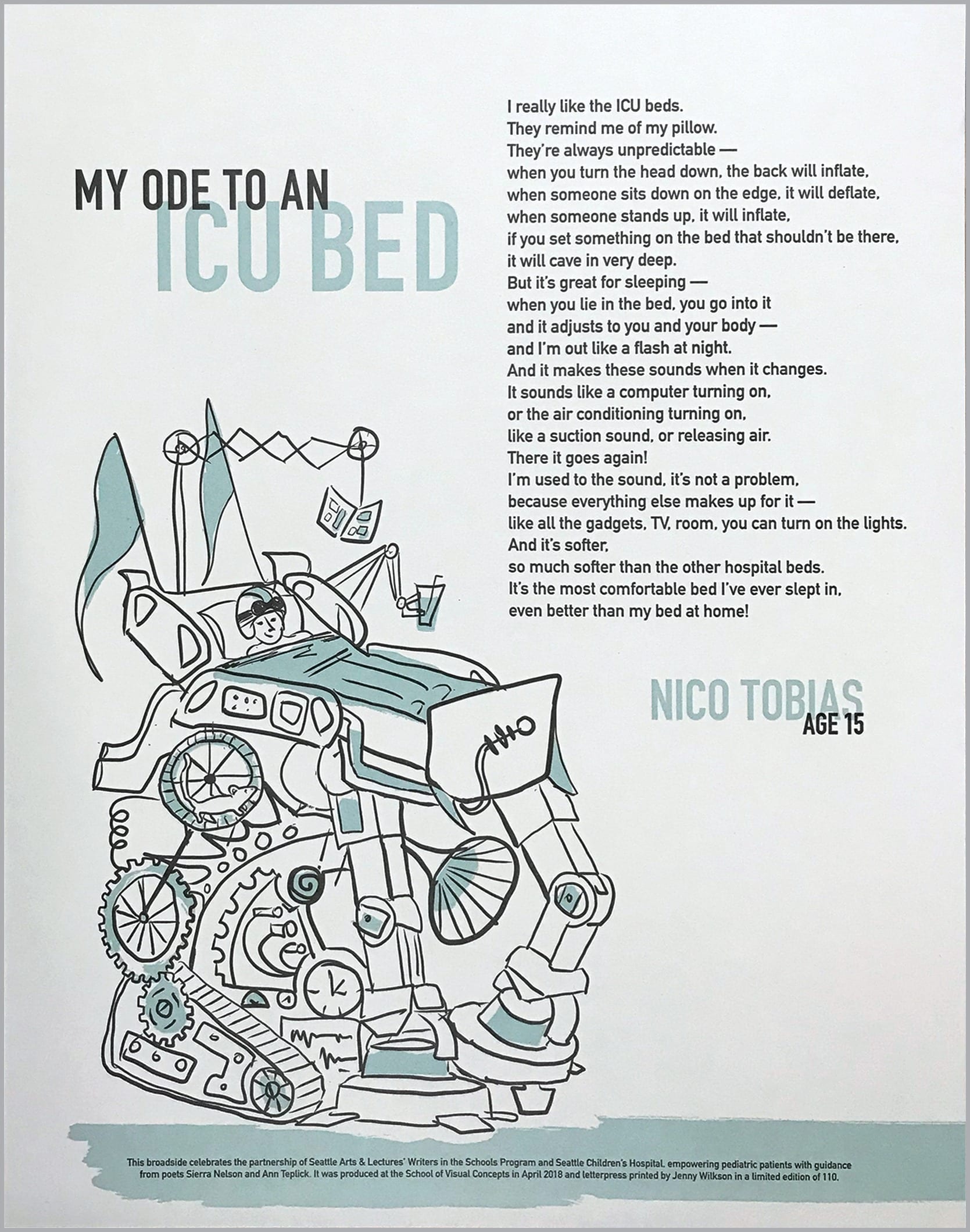

Jenny: The only time that happened for me was when we did [the broadside poem about the] hospital bed by Nico Tobias. I didn’t meet him during the creative process and, it’s funny, I never pick a poem during the poem selection; I let the other printers choose first. I can see why that poem on the surface wasn’t chosen because it was about an ICU bed. I’m sure everybody was like, I’m gonna have to illustrate an ICU bed—I don’t want to do that. [But the poem] was like, This is everything my ICU bed can do.

I have kids and I totally get where that was coming from. That ICU bed was full of wonder. He loved all the features. So I was, like, I can draw an ICU bed and I’m gonna make it as wonderful as he thinks it is. And, you know, we added tank wheels to it and articulating arms and made it this steampunk thing, and it ended up being the poem featured at the WITS luncheon.

Gabriela: Yes! I remember that poem!

Jenny: I met him after this whole process. Other printers make a point of visiting the hospital to meet their poet and some strike up a rapport via the family and social media, especially with the teenagers. It’s really neat to see how they connect and learn about their preferences in subject matter and color. Some printers really collaborate with their poets.

Gabriela: How do these poems start?

Sierra: In some cases, there are prompts. When I work with a student—which could be age four to twenty-four in a given day—I have a million different prompts at the ready. Some are, like, “I love writing. I love writing poetry,” or, “I’ve always wanted to do that.” They just line up. Others are like, “Is this more school? No.” So I’m like, “Well, what about a notebook?” I give away notebooks, sticker paper, office supplies, and build rapport from there. Or, I’ll say, “Just talk to me and I’ll write it down.” We have to be nimble. Then, depending on what what’s happening for folks physically, or if they’re more visual/aural, there’s all kinds of things we’re navigating within, too.

Two years ago, a student, Erin, had this amazing riddle about a turkey. She loved turkeys, and her room was full of stuffed animal turkeys, and they all had names. They all had different badges, like medical badges, and they had different responsibilities. So there’s this poem—it was a riddle—and the artists did a beautiful job of suggesting turkeys through patterning, but it doesn’t give it away. The artists delivered it in person, and that was one of the more remarkable times—not only was she so excited to see her poem, she really approved of how there was a hint, but it didn’t give it away. The integrity of the riddle was kept intact, but still had a visual celebration of the turkey.

Erin read the whole portfolio, each poem, out loud. Then she reflected on what each poet might have been thinking and noted the design. It was incredible. We had a beautiful afternoon of looking through the whole portfolio, and it was amazing seeing it through her eyes. Things she noted in the poems as a fellow patient and youth—she was seeing things in the poems that stood out to her in a way that struck me. It was really amazing to have had that shared time.

Gabriela: Have you ever worked with students who had a change of heart about poetry during the time you worked with them? Maybe they didn’t like it so much at first?

Ann: For sure. A student, about fifteen-years-old, came to the classroom each week with his hood up and his head down. I had never worked with him. He was always off in the corner doing his own thing, and he’d never join the poetry circle. After a time, the teachers asked me to work with him in his room. I had been curious about him. We talked about expressing ourselves through writing and how that often lightens the heaviness of our lives. How the arts do that. I asked if he would like to do some writing together. I didn’t use the word “poetry.” Before he could answer, and it looked like he was on the verge of a polite decline, I added, “You know that you do.” He nodded, smiled, pushed off his hood and wrote a wonderful poem that graced a letterpress edition a few years ago.

“I asked if he would like to do some writing together. I didn’t use the word poetry. I added, ‘You know you do.’”

Gabriela: What happens after the portfolios come out? Are you in touch with the poets or their families?

Sierra: A little bit. The kids go into the world, and sometimes you hear back, sometimes from the families about how meaningful the time was or about continued creative things. Often, there is another opportunity for readings because we do have readings at Children’s Hospital where we invite a wider group of folks to come back if they’re outpatient or beyond their treatment. Then we hear how they’ve continued to read and write.

Ann: Nico is a huge fan of WITS, and kind of a spokesperson for the program. He’s a great orator. A great young man. We work with young writers who have super busy days and super complex lives. You go into the classroom and into their hospital rooms—you don’t know the mood or anything about the layers of what’s going on. But they sit taller and prouder when they’ve had the opportunity to express, through writing, who they are, and the emotions of what they’re going through.

Sierra: Yeah. Starting with the second portfolio, we have a tradition to ask a student from the previous portfolio to write an introduction about what writing means to them, or what the portfolio meant to them. That has been a really sweet way of connecting back. One student I worked with, Noelia, I met with her at the library several times to think about her intro and help her craft it, and that was really wonderful. To see her and her family again and meet at the King County Library, we could continue to connect and hear how her writing was going and that she was excited about poetry. I think it’s often this bright moment in a very dark time, but poetry can be something they carry forward into their lives beyond the hospital. That means a lot to me.

“I think it’s often this bright moment in a very dark time, but poetry can be something they carry forward into their lives beyond the hospital. That means a lot to me.”

Gabriela: How has this experience changed you as artists and as humans?

Jenny: This project has reinforced that, to find a place for letterpress printing in our community, you have to make sure that it is meaningful, that the projects you’re doing are valuable to others, that they give the printer a sense that they’re doing good. This was the first project that we did as a community of printers that gave us the feeling that we were doing good. Since then, we’ve taken on other collaborations in the community and other projects that have leveraged lots of printers together to do good, but this one set the tone. It taught us that for us to continue to be relevant as an art form—because letterpress printing is a dying technology, right?—for us to keep it relevant, we need to keep it meaningful. This was the perfect project where something tangible and valuable needed to be created for these poems to last in people’s consciousness, and to build legacy for these children. And to give Seattle Arts & Lectures and Writers in the Schools something tangible and visual to show for their amazing programming.

Ann:Once again, I’ve become stronger, more resilient, and more compassionate. The children and teens we work with are our teachers, our guides.

I walk through the halls of the hospital, with a noisy internal monologue that doesn’t know how to turn itself off. I continue to ask myself, why are there so many kids here? Why are so many kids ill? But I don’t talk about it. Once, when I first started at Children’s, I did talk about it. Maybe it was the audible sigh, with my facial expression of sadness. The woman in conversation said, “You can’t do that here. You can do that in your car, or once you’ve left the building and are outside.” I’ll never forget that. It’s an honor to spread the love of poetry at Seattle Children’s Hospital, where the youth and their families, and everyone that orbits around them, in service to them, are Super Heroes.

“It’s an honor to spread the love of poetry at Seattle Children’s Hospital, where the youth and their families, and everyone that orbits around them, in service to them, are Super Heroes.”

Sierra: Sometimes, as a writer and an artist, I wonder, what is it for? Like, what good does art do? Sometimes, it does so little. I wish it could change everything or change something. But then, I have witnessed what it can do in a way that restores my belief. To see a young writer write toward their experience, even if it is heartbreaking or scary or devastating, they’re able to express it on the page. I see a tangible shift in them, a sense of relief, to have become a creator in that moment—to take that experience and express it does shift things. It doesn’t change anything that’s happened or is happening, but it does create space where they’re able to sense relief and connection, the potential of being able to have said it to another person, to have said it on the page. The amazing ability of our imaginations to take us outside of a space.

Sometimes, that is the miracle that occurs. It can be just as powerful, or another kind of power, to use your imagination to be somewhere else that’s not a hospital, that’s just your favorite colors and creatures. You create space for physical relief, to be outside of your immediate experience and body and pain for a moment, space that you can go into—and others who read it can enter that same magical space. It’s incredible that we can share these spaces with other people. That has renewed my faith in what writing can be.

“You create space for physical relief, to be outside of your immediate experience and body and pain for a moment, space that you can go into—and others who read it can enter that same magical space.”

Gabriela Denise Frank is a literary artist whose work has appeared in galleries, storefronts, libraries, anthologies, magazines, podcasts, and online. Her essays and fiction have been published in True Story, Hunger Mountain, Bayou, Baltimore Review, Crab Creek Review, Pembroke, The Normal School, and The Rumpus. A Jack Straw Writer and Artist Trust EDGE alumna, Gabriela’s work is supported by 4Culture, Mineral School, Vermont Studio Center, Jack Straw, Invoking the Pause, and the Civita Institute. www.gabrieladenisefrank.com