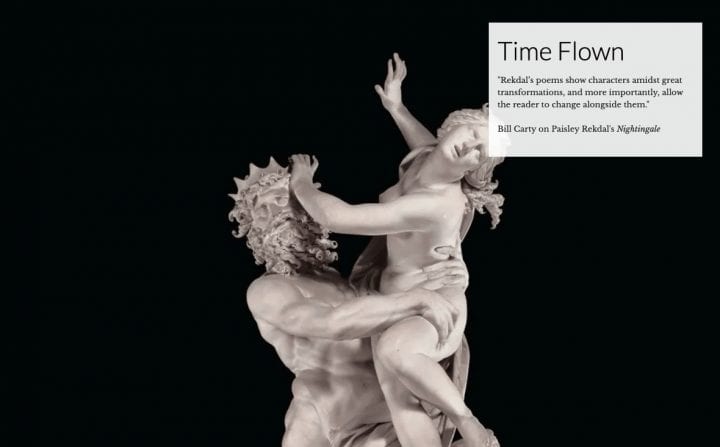

Time Flown

January 29, 2020

This essay is part of a series in which Poetry Northwest partners with Seattle Arts & Lectures to present reflections on visiting writers from the SAL Poetry Series. At 7:30 p.m. on Thursday, February 6, Paisley Rekdal will read at Hugo House. Tickets are still available!

By Bill Carty, Senior Editor at Poetry Northwest

Pythagoras’s greatest influence upon his contemporaries, according to classicist Carl Huffman, was not the geometric theorem for which he is now famous (and which pre-dated him by a thousand years), but rather his belief in metempsychosis, the transfer of an essential nature from one body to another. It makes sense then that Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, seeking to sing of “bodies becoming other bodies,” dedicates nearly four hundred lines of the epic’s final book to a speech from Pythagoras, an elucidation of his philosophy in which he states,

in all this world, no thing can keep

its form. For all things flow; all things are born

to change their shapes. And time itself is like

a river, flowing on an endless course.

Nightingale, Paisley Rekdal’s collection of poems published by Copper Canyon in 2019, draws extensively from Ovid and other mythologies, and fittingly concludes with a poem titled “Pythagorean.” Like many of the poems in Nightingale, this one adopts a mythological figure for the title, and then introduces characters in a recognizably modern world. In this case, the poem is set at a dinner party, the point of view shifting among perspectives, a portrait of characters lost in misapprehension of one another. Within the somewhat distant third person narration of the poem, we find moments of deep interiority. The dinner host’s proposition that “humankind’s distinguishing feature / must be empathy” causes a young lawyer at the table to think of the term in relation to his mother’s and his own “heritable need” for alcohol:

. . . Empathy

was not the starting point of change

for her but fear: sobriety seemed only

to clarify an essential indifference

she must have felt . . .

No sooner have we settled into this perspective than the poem shifts again. A mathematician present makes a flirtatious comment to a professor, while his wife imagines potential transgression:

. . . flushing now, thinking of it, bemused

by this jealousy that she alone

has authored. Perhaps this

is the defining feature of humanity,

she thinks: the capacity to imagine

some small cruelty and take pleasure in it . . .

In Nightingale, as with Ovid’s epic, pleasure is wedded to cruelty, beauty to violence, human life to change. Elsewhere in Metamorphoses, Pythagoras says, “Our bodies undergo / the never-resting changes: what we were / and what we are today is not to be / tomorrow.” Rekdal’s poems show characters amidst great transformations, and more importantly, allow the reader to change alongside them. A sense of self and our sense of others shift moment to moment, based on new inputs, new intelligence. In “Pythagoras,” what might begin as distaste for the mathematician’s bombast and indiscretion changes when the poem switches to his perspective: the starlings of an early metaphor seemed like an obnoxious linguistic flourish, meant to impress, but through his perspective, we learn the image of the birds to be imbued with the loss of a now-deceased girlfriend, as well as a moment of tranquility with his wife . . .

Read more on Poetry Northwest.