Yes, And . . . God: Humanity’s Muse

November 13, 2017

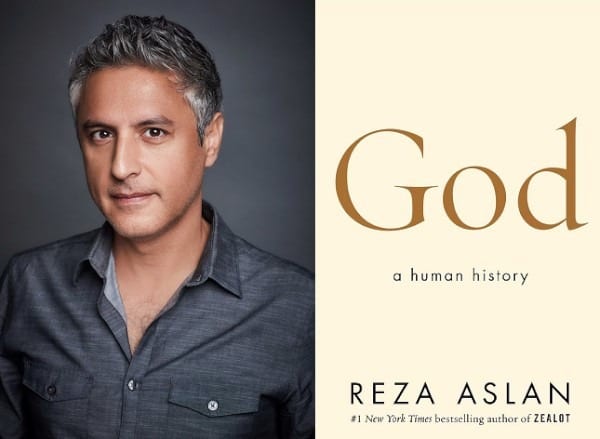

Tomorrow, Tuesday, November 14th, scholar of religions Reza Aslan will give an original, multi-media presentation on his new book, God: A Human History, an interfaith exploration of how different ideas of God have both united and divided us for millennia, as part of our 2017/18 SAL Presents Series. Tickets are still available here!

In anticipation of Reza’s talk, WITS Writer-in-Residence Cody Pherigo presents us with his reflections after reading God: A Human History, a book he found to deeply resonate with the human impulse to be creative. (Plus, a Reza Aslan-inspired writing prompt!)

By: Cody Pherigo, WITS Writer-in-Residence

God: A Human History by Reza Aslan traces a paradoxical tight-rope path from our prehistoric ancestors to the present, and the many ways we’ve conceived of and related to god(s). He opens with an introduction titled “In Our Image,” and immediately I knew this would be, for me at least, a path that also echoes the creative writing process.

While much of the text is classically academic and thus devoted to (as any research worth its salt and sugar) dozens of pages of endnotes, I detect, too, the shadow of a poet. One of my favorites lines comes early on, as he renders a new story of Adam and Eve. Aslan says that while Adam may take up to a week to hunt and bring home a lump of meat, Eve and their children gather daily a prorated equivalent amount of food—plants, fish (netted), small prey (trapped and clubbed), and nuts, which have the same amount of protein per pound as meat—plus, “nuts do not fight back” (save for those with allergies).

We begin with Part 1: The Embodied Soul, where the idea of a “soul” emerges as an innate feeling and deep knowing, the source of our “religious impulse.” Here, Aslan suggests what may be humanity’s first belief: a kind of animism, or, I’d offer imagination. What I noticed for the duration of reading God: A Human History is a continuity of pillars within the creative process, from symbols and metaphors to the development of language, writing, and the problem/blessing/turn of translation. To me, these creative “bones” parallel and mirror the religious impulse, what Aslan shows is an impulse that is at the root of what it is to be human.

One of the first gathering places for spiritual experiences were caves—all over the world, they have been been adorned with drawings placed so intentionally onto the cave walls that, Aslan suggests, “The cave becomes a mythogram; it is meant to be read, the way one reads scripture.” Here, too, was found evidence of animal bones burned, as a sort of incense or “mediating element.” What’s interesting here is the metaphor and resilience of bones, how they act as a stand-in for bodies past, bodies passed down the way words and stories are passed down, and both for posterity. Or, the repetition of a story—the idea of a soul making its way from body to body, retelling itself.

Later, he cites a key turning point in humanity’s lifestyle: the switch from hunter-gather to farmer, which, he posits, may revolve around the building of our first major temple, the Göbekli Tepe, as the center of “the birth of organized religion.” This transition in human lifestyle was a “revolution of symbols” (Aslan credits Jacques Cauvin here). I wonder, too, how this changed our relationship with metaphors, as humans have put themselves in the “center of the spiritual plane,” where humanity’s story about god seems to switch from fiction to memoir.

Eventually, we come to write, and the abstract becomes concrete: “Writing changes everything. Its development marks the dividing line between prehistory and history,” Aslan says. I would add that once this lineage of writing began, so does the publication and “selling” of religious texts, and their subsequent dissemination. A readership develops. A density of language, too, and definition spreads. God: A Human History seems to bring forth issues of translation at each turn in our species’ evolution, both in how and what god(s) were named, interpretation from century to century, culture to culture, and the riddle of etymology—a word’s history, and thus, its meaning(s).

Aslan chronicles some major early attempts at monotheism, and to a degree, the push for an un-humanized god, and how both failed intensely and often violently. Another parallel trait in this book as it relates to the creative impulse, or process, is simply: failure. Humanity has tried through many iterations of religion (and religious and philosophical scholars have stabbed at theories), and failed, over and over, to be satisfied, or at least, to stay. But, it seems, these attempts, these essays, were part of a developing, devotional pedagogy of and for our species—within that process is the practice and repetition of faith. Yet, I also think of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein creation/destruction mythos merged with the writing advice to “kill your darlings.” (Thanks, Rebecca Brown). Or: the impulse to revise.

One of Aslan’s most intriguing accounts for the “humanized god” pattern is politicomorphism, where, as societies evolve and change, so do humanity’s ideas of god(s). Put another way: “the divinization of earthly politics.” It’s convenient, particularly for people in power, to revise their religion, which reminds me of censorship: this is what we do and don’t do now, and if you won’t adapt and conform, be gone.

In addition to outlining the phenomena and consequences of politicomorphism, Aslan highlights a few major cognitive traits that account for how humans have personalized the divine: HADD (Hypersensitivity Agency Detection Device—we are hardwired to attribute human agency to our environment) and the Theory of Mind (we model our assumptions of others based off of ourselves). Both link naturally to our religious impulse. He offers a mini-story to summarize these:

Theory of Mind makes Eve prone to view nonhumans who exhibit human traits in the same way she views actual humans . . . She is just as likely to attribute a soul to certain inanimate things. Put another way, if the tree has a ‘face’ as Eve does, it must, like Eve, also have a ‘soul.’

As a poet and math nerd, I particularly appreciate the structure of God: A Human History, which, like many poems, reinforces his thesis. Divided into three parts, with a subsequent layering of three chapters per part, the book seems to model the culminating chapters: “God as One,” “God as Three,” and “God as All.” With the accretion of each chapter, what resonates is a definitive and resounding: “Yes, and . . .” A place for paradox, for opposites to exist and, within that, interdependence.

At the end of the book, we meet the Sufi poet Rumi and make our way full circle to pantheism, which Aslan says has the capacity to contain all of the arguments and attempts at religion before us. We are offered the idea that humans are a metaphor for god. I would say the religious impulse shares a coin with the impulse to create, a holy trinity of: the Writer, the Muses, and the Writing, which falls into its own kind of pantheon.

And so, I will in turn end with a small pantheon of personal offerings inspired by God: A Human History, along with a brief lesson and writing prompt:

1. Michael Franti & Spearhead’s “Every Single Soul” from his 2001 album “Stay Human,” which loosely echoes Aslan’s pantheistic conclusion: Every=All, Single=One, Soul=Soul “is a poem.”

2. Two images of Pan, the goat god, or as Aslan might say, a “Lord of the Beasts.”

3. My poem, “When My Body is a Metaphor for Faith,” recently published in THEM, an online literary journal (page 22).

Writing Lesson

Consider the ways that metaphor, as an act of image-ination, relates to writing genre, genre as “a kind” of. As Kim Addonizio says in Ordinary Genius, “Metaphor (from the Greek metaphora, ‘transference’) speaks of one thing in terms of another, creating a kind of energy field, what I think of as “the shimmer.” As one thing substituting in for another, and another, and another, until perhaps the thing(s) merge, mirror, awaken, and relate.

Write 3 different versions of the same story or subject, the change being primarily your version of the genre. Choose from one of the following prompts, pulled from God: A Human History, and use it for all three versions below.

Prompts:

- Begin with: [ ] changes everything.

- Beliefs do not fossilize.

- Write about various “idols” you’ve prayed to or for.

Version 1: Memoir

- Keep this in the first person

- Personalize the details, tying them to your past and present, to your thoughts and feelings

- Experiment with time—e.g. write it strictly chronological, OR jump around, layering different time periods to create tension

Version 2: Poem

- Play with the form in your notebook—e.g. casting line breaks as you write, and use enjambment

- Let your ear guide you, as if this were a song. Let sounds—alliteration, rhyme, etc.—thrive

- Pick a word or short phrase to repeat throughout the poem, to ground it and also broaden the word/phrase’s meaning

Version 3: Creative Nonfiction or Journalism

- Include some kind of critical, “objective” analysis, a rendering of fact

- Pay close attention to your verbs and let them do the heavy lifting

- Include dialogue and/or quoted text

Cody Pherigo is a queer writer from Kalamazoo, MI. His studies at Bent Writing Institute and Goddard College convinced him that poets are politicians in the most humane sense of the word. Cody has self-published 2 chapbooks, and is a 2016 Ruth Stone Poetry Prize finalist. In 2016, he was awarded a 4Culture Artists Grant for a project on trans resilience.

Cody Pherigo is a queer writer from Kalamazoo, MI. His studies at Bent Writing Institute and Goddard College convinced him that poets are politicians in the most humane sense of the word. Cody has self-published 2 chapbooks, and is a 2016 Ruth Stone Poetry Prize finalist. In 2016, he was awarded a 4Culture Artists Grant for a project on trans resilience.