Our Most Memorable Books of 2020

December 21, 2020

Today is the shortest day of the year in Seattle—the sun rose at 7:55 a.m., and it will set at 4:21 p.m. In our opinion, that leaves us with two clear bright spots in our day:

First, we can spend the darkest day reflecting on the best parts of a difficult year and anticipating what is to come—it only gets lighter and brighter from here! Second, if there was ever an excuse to cancel your virtual plans, fill the house with candle and lamplight, and pull out a book, that time is now.

In celebration of the winter solstice and the holiday reading time to come, here are the books from the SAL family—staff, board, volunteers, and more—that helped us through 2020. We hope you find these titles as grounding, illuminating, diverting, and mending as we did.

Candace Barron, SAL Board Member

Subduction by Kristen Millares Young. Not only because Kristen is one of my dear friends (shameless plug)—the way she uses the individual narratives of two people to illustrate the importance of story-telling to history and culture goes beyond a tale about love and individual triumph over adversity. Subduction brings to life the ways of the Makah, and by extension, Indigenous cultures, in a respectful narrative that demonstrates both the uplifting and destructive power that words can wield on a person and a people.

Sarah Burns, Event & Corporate Giving Manager

The Overstory by Richard Powers. This book changed the way I look at trees and think about the future of our planet. Beautiful and haunting images replay in my mind. The intertwining character stories are enthralling and the message about climate change galvanizing. I have ”virtually” pressed this book into many people’s hands. A crucial and inspiring read to savor and discuss.

Letitia Cain, Marketing Coordinator

Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo. It’s a tricky question to answer what’s the best book you’ve read in 2020. Fiction, poetry, non-fiction, mystery, cookbook? I’ve decided to define ‘best’ as the book that still lingers with me, that my mind returns to over and over. A book that I did not want to put down and is also beautifully written. A book that challenges my idea of what a good book is or can be. Girl, Woman, Other does all of those things and more. It opens with this dedication: “For the sisters & the sistas & the sistahs & the sistren & the women & the womxn & the wimmin & the womyn & our brethren & our bredrin & our brothers & our bruvs & our men & our mandem & the LGBTQI+ members of the human family.” The first page set my expectations, and what unfolds is a beautiful, polyphonic kaleidoscope of intertwining stories that still holds me entranced. A must read!

Jenn St. Claire, SAL Board Alumna

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Lathe Of Heaven. Thank goodness for book groups and their ability to push you out of your reading comfort zone. I’ve eyed up Le Guin’s essays, but hadn’t given much thought to picking up her fiction until it was “assigned” reading. This book was incredible. Written in 1971, it reads like it was written last year (sadly). We’ve not made much progress on war/violence/racism and we’ve surpassed worst fears with climate change. While this was unsettling to read, her book is a fascinating notion—a man whose dreams change reality—the past and the future and he’s the only one aware of the change. A doctor assigned to treat this reality dream changer—tries to use these gifts to make the world a better place and surprise—power corrupts us all, and the goal becomes the power itself rather than what it can accomplish. Also, aliens. This book is surprisingly sweet in the midst of all the terror and pain. Kind of like life. The good is always there if you’re willing to see it.

Alicia Craven, WITS Program Director

Stormwarning by Kristín Svava Tómasdóttir. This was a book of poetry read with my Icelandic book club. It was written in 2018, but felt incredibly resonant in this moment: “This collection of poetry offers a very different view of the Icelandic winter than that of the magical north—a feeling of being confined to your home and forced to keep your own company while waiting out the storm. The speakers of the poems revel in their melancholy and loneliness with acute self-awareness, addressing the humdrum of the everyday and the pettiness of lives lead online. Yet, the tone is light, ironic and funny, as if the speakers can’t keep from smirking at their own theatrical miseries. The translation was recently nominated for the PEN America Translation Prize and is presented in a dual language format” (from the publisher).

Piper Daugharty, WITS Program Associate

Bright Archive by Sarah Minor. This experimental, hybrid essay collection expanded my own ideas of what an essay can and should be. Relying on structures and content of buildings, rivers, archives, laundry chutes, knots, maps, and family mythology. Minor builds, excavates, and knits her own personal histories with hard-stretched research she’s already deeply internalized, and so easily embodies connective tissue. Never did I feel like she wouldn’t guide me towards connection, intimacy, and restraint. It is at once ghost story, midwestern funeral, and confession.

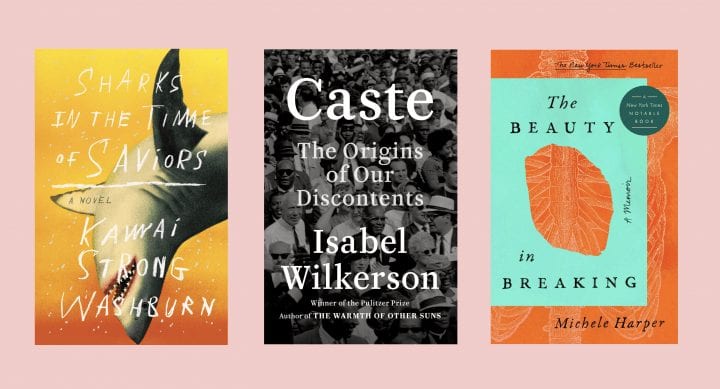

Sharks in the Time of Saviors by Kawai Strong Washburn. This lyrical debut is, in my personal opinion, the perfect novel. Lyrical, gritty, and with deep connection to Indigenous livelihood, each character in this novel urgently survives in their own way. I couldn’t put this down, which, in a year of constant doom scrolling and distraction, felt like the perfect escape towards a hopeful future, one in which Indigenous communities have power over their communities’ autonomy and land stewardship.

Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss. Compact, creepy, and sinister, this tiny novella had me devouring (until the end, when I had to slow myself down and savor)! In a modern telling of settler-colonial mentality and hypermasculinity that romanticizes a past which we no longer have access to, the story of a young girl in a familial situation of normalized abuse screams down a railroad track towards inevitable sacrifice.

Ruth Dickey, Executive Director

The Beauty in Breaking: A Memoir by Michele Harper. I absolutely loved this book, which explores Dr. Harper’s work as an emergency room physician and her own history of family violence. At turns poetic, heartbreaking, and deeply moving, the book illuminates the ways that racism skews our medical system and the ways systems and individuals respond to trauma. Through interwoven stories, The Beauty in Breaking paints a nuanced portrait of the power of presence, and the possibility of healing, which feels like both a map and a salve in these troubled times.

Lynn Dissinger, Volunteer

Deep River by Karl Marlantes. In the first days of March, after screening a Finnish film at the Nordic Lights Film Festival, a film friend recommended Deep River by Karl Marlantes. I picked up the book at the Seattle Library that week and was initially intimidated by the 700+ page heft of this novel. Then the realization set in that life as I knew it was turned upside down and I would be stuck at home for the foreseeable future. Suddenly a long, engaging story about Finnish immigrants working in the logging industry in early twentieth century Pacific Northwest communities was the perfect reading choice. I enjoyed the local history as well as the engaging characters, particularly the strong female protagonist.

Jennifer Duval, Volunteer

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson. I just looked at my book list for this year and so far, I’ve read 31 books in 2020. When asked which book was most memorable, I think that I would have to say Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. This book felt so incredibly timely and apropos of the insanity happening all around us this summer; and Wilkerson was able to lay forth a brilliant argument for how we got to this place. Her use of historical facts, quotes, personal observations, and experiences, combined with her superb writing style made for an excellent, though at times difficult, read. I have recommended this book to many friends, and believe that it’s a great starting point for the critical conversation about race in America.

Mary Kay Feather, Volunteer

The Hanky of Pippin’s Daughter by Rosmarie Waldrop. The introduction by Ben Lerner recounts youngest daughter Lucy Seifert’s recap of this story of infidelity in her parents’ tempestuous German marriage in the 1930s, though letters between their three daughters, two of whom are twins, perhaps fathered by Mother Frederika’s lover Franz, a Jewish musician. With the advent of the Nazi Party, Josef, the father, fears the twins will be identified as Jews and goes to great lengths to protect them. The book is structured into many sections with headings which sometimes confused, but I was rewarded by the beautiful language and sensuality, the music references, and amusing bits such as Lucy’s musician lover, Laff. Much of the story takes place in Kitzingen. The site of the town was determined by a hanky, which was dropped from a window of Castle Schwanberg by the daughter of Pippin the Short. This book describes how one grievous action can alter a life.

Kathryn Flanagan, Volunteer

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson. I have read many books in the past five years regarding Black Lives Matter. This is the one that continues to live in heart and soul. We cannot fall back asleep.

Laura Gamache, WITS Writer

The Bear by Andrew Krivak. In the midst of human-caused horrors–climate crisis, racist violence, the pandemic—it was comforting to read that the earth will thrive after humans, and the last person will learn to live cooperatively with all the other beings around her.

Debra Godfrey, Volunteer

The Death and Life of Aida Hernandez by Aaron Bobrow-Strain. The U.S.-Mexico border has been much in the news and much on my mind these last couple of years, and this book gave me an understanding of how drastically the meaning and enforcement of that imaginary line has changed in just a few years. Aida’s experience is only barely comprehensible to her mother, as just one generation has seen tremendous shifts in attitudes and access. I learned a great deal about life along the border through the twentieth century, and Aida’s story is heart-wrenching and resonates in me months after reading it last winter.

Christina Gould, Patron Services Manager

Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents by Octavia E Butler. I shy away from reading dystopian novels but Book Bingo pushed me into that realm and I chose to read Parable of the Sower, the first of a two-part series, for the Afrofuturism square. I could not get this novel out of my head so I had to read Parable of the Talents as well, and both are my most memorable books of 2020. Parable of the Sower was published in 1993, it opens in LA in 2024; global warming has brought drought, fresh water is scarce, fires are common, people live in walled communities, distrust the police and each other, and a Presidential candidate has been elected based on his promises to dismantle government programs and bring back jobs. Parable of the Talents, published in 1998, begins in 2032; a new Presidential candidate, a religious zealot, is running on a platform to “make America great again.” By now, the oppression of women is extreme and forms of indentured servitude and slavery are common. For sheer prescience, Butler’s novels seem unmatched; her insights and predictions uncanny. Her view that social progress is reversible is a real lesson that must be remembered. These novels reinforced that I must stay awake and pay attention to the social, cultural, and political doings around me.

Rebecca Hoogs, Associate Director

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett. Early last winter, in The Before, I listened to The Dutch House read by Tom Hanks. It was such an immersive experience to spend a week or two of drive time in a cocoon of the story of a house and the brother and sister who once lived there. This book had an almost slow or old-fashioned feeling to it, or maybe that’s just Hanks’ voice, but something about the experience of listening to the book was quietly engrossing. I couldn’t wait to embark upon my long commute each night. I read lots of books this year; was this the best book? I’m not sure, but it’s an experience that I am nostalgic for now.

Liz Keenan, Volunteer

The Resurrection of Joan Ashby by Cherise Wolas. When I read The Resurrection of Joan Ashby back in early March, I remember thinking this is a novel to return to again and again—I didn’t want to lose contact with the main protagonist, Joan Ashby, after playing such a big part in her life as her reader. I was hooked from the very first page and read the 500+ page novel over a weekend, devouring it slowly, not wanting it to end, because I have a passion for reading books that tell stories about writers and stories within stories. It is now December, and I still think about this book and wonder about the character’s future, like an old friend who wants to spend more time with her and catch up with her joys, sorrows, disappointments, and conflicts. Although it is a chunky book, don’t let that put you off—the story flows beautifully and grabs the attention immediately.

Patricia Kiyono, SAL Board Member

Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance by Edgar Villanueva. If you want to refresh your approach to philanthropy in this time of social reckoning, read Edgar Villanueva’s Decolonizing Wealth. As a veteran of the philanthropy sector, and a Native American, Villanueva chides charitable foundations for perpetuating their colonizing power: granting money earned in an inequitable system to patch problems created by an inequitable system. As many private foundations give the minimum 5% of their wealth away each year, and only about 7% of that money goes to nonwhite communities, I hope people heed Villanueva’s advice to shift the balance and “listen in color.”

Corinne Manning, WITS Writer-in-Residence

The Great Offshore Grounds by Vanessa Veselka. A book about inheritance and colonial history. Two white-identified sisters born into poverty in Seattle–and the product of a radical feminist polyamorous love affair—go on trip to find out which of the two women their biological father impregnated is each of their mothers. Characters in the book also include the ghosts of Sir Walter Raleigh and LeJeune.

Kris Morada, Volunteer

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo. The protagonist of the novel is an ordinary middle-class mom in Korea. A Korean “everywoman” who suffers a dissociative break from the misogyny she faces within her family and in Korean society at large, Kim Jiyoung’s experiences nonetheless felt familiar for me as an American reader. The novel was published here in the U.S. amid a presidential race that highlighted our distinctly American brand of gender inequality. Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 broke my heart as only great stories do, and inspired me to explore other Korean literature as well.

Cindy Seramur, Volunteer

The Choice by Edith Eger. I didn’t have to think long for the most memorable book I read in 2020: The Choice, a memoir by Edith Eger, really stands out. Any self-pity I might have in our pandemic crisis was quickly put to rest after reading what Edith Eger has withstood.

Leanne Skooglund, Development Director

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi is hands down the most memorable book I’ve read this year. In this debut novel, Gyasi is a mesmerizing storyteller, leading the reader through many generations of the descendants of half-sisters Esi and Effia, born in the mid-1700s in Ghana. The story begins when Effia is married off to a British slave trader as his “wench,” and he enslaves Esi, shipping her in a horrific journey to America. The strength, resilience, heartbreak, and struggle of Effia and Esi and their generations of offspring, all trapped within a violent and relentless system of racist oppression, will stay with me for a very long time as I continue on my own journey of becoming an effective ally in dismantling that injustice.

Cara Sutherland, Designer

Network Effect by Martha Wells. The first full length stand-alone novel in her Murderbot series. I love this character and these books. They are dark, funny, and nerdy. The books explore ideas about personhood and identity against a future where humanity has expanded into distant space and corporations have become quasi-authoritarian, exploitive, capitalist nation-states. All Murderbot (a self-hacking AI security unit) wants to do is watch thousands of hours of soap operas and be left alone. I burned through all four novellas and two short stories last year in two days (winter vacation) and immediately pre-ordered the novel. I already have the next novel coming out next spring pre-ordered. They are so much fun.

The Second Founding by Eric Foner. Believe it or not I was a History major in college and my area of interest (which I had intended to pursue in grad school once upon a time) was the Civil War and Reconstruction. Foner’s new book specifically studies the creation, ratification, implementation and subsequent interpretations of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. It is a fascinating and sometimes infuriating history made more frustrating by the debates happening around citizenship and voting rights today.

The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin. So good! Another author subverting the racist themes and imagery and legacy of Lovecraft in modern stories. Sci-fi that redefines and centers women, queer people, and minorities as the hero and confront the caustic legacy of twentieth century Sci-fi boys club storytelling.

Jennifer Wong, SAL Board Member

The Coffin Path by Katherine Clements. My favorite book of 2020, hands down, is the spine-tingling, hauntingly atmospheric, gothic historical novel, The Coffin Path by Katherine Clements. It is the perfect ghost story and gave me that rare feeling I most long for when reading, which is to get so lost in a story that I get secretly irritated by anything that pulls me away from it. I didn’t wait until just before bed to read it. I snuck in reading sessions in the morning and in the afternoons. The Coffin Path is set in Northern England’s moorlands during the late seventeenth century and features an ancient pile of a mansion, Scarcross Hall, which sits on an austere moor top scoured by storms and crowned with standing stones. The heroine, Mercy, tries to keep her farm and her sanity while rumor, gossip, old secrets, and tales of witchcraft abound. It’s an engrossing novel of family and the primordial pull of the land and one that l think of though it has been months since I turned the last page. I miss Mercy and I still wonder about her.