An Essay from “Seismic” by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore

October 10, 2020

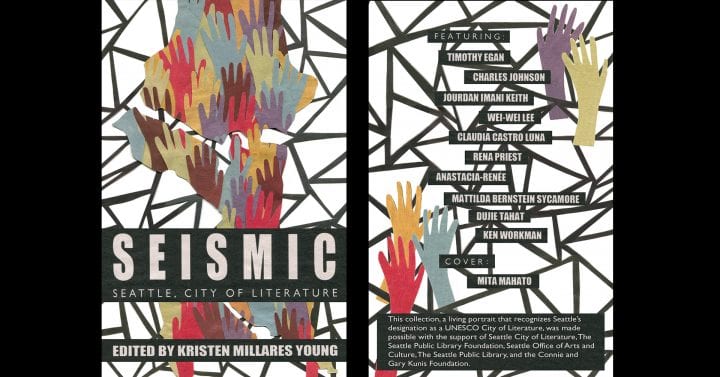

This essay appears in Seismic: Seattle, City of Literature, an anthology edited by Kristen Millares Young, featuring writers from all across the city. Seattle was designated a UNESCO City of Literature in 2017 and has been working as part of the international network since then.

Seismic is a collection that asks writers to consider what the designation means for our city and how literature might be an agent of change. Learn more and download your copy now!

By Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore

I moved to Seattle in 2012, a year before the publication of my memoir, The End of San Francisco, and people would ask: are you going to write The End of Seattle next? I would laugh—I had lived in Seattle two times before. The first was for a month in 1994, when I was 20, and I carried The Courage to Heal around like it might save me. JoAnne and I shared a bed for a month, and it never felt crowded—when something like this happens to you in a nonsexual way, you know it will last forever. Soon enough JoAnne moved to San Francisco to live with me, and even if I tell you she died only a year later, this doesn’t mean we didn’t have a life together, it just means it ended way too soon, after the hospital refused to care for her because she was a junkie.

The first time I ever felt relaxed was in Seattle, sharing anger like a hug and when I came back for a little over a year in 1996 and ’97 I felt that calm too but it was too calm so I moved to New York. And when I moved back to Seattle in 2012, it felt like it hadn’t changed nearly as much as any of the other cities I knew and that’s why I laughed.

Seattle to me has always been a middle-class town, and even if this is everything I hate about it, it might also be part of what has made it feel calm. Six years ago, I may have laughed when people asked me if I was writing The End of Seattle, but there is no question that we are living it now. Seattle is now a city of displacement and desperation, where rent has basically doubled in seven years and we have no meaningful protections, where even people against gentrification say of course they support increasing the density. But what kind of density are they supporting? A density of overpriced crap; a density of bland homogenization; a density of corporate exploitation masquerading as necessary growth.

Everyone talks about the need for affordable housing, while the city shuts down the largest public housing project, displacing hundreds of families and destroying the country’s first mixed-race housing project to make way for a billionaire to build luxury apartments. How did they do this? By changing the zoning to increase the density. When developers control the language, everyone else loses. “Affordable housing” for middle-class people becomes the priority instead of low-income housing for poor people. “Increasing the density” of corporate profit becomes the rule instead of expanding the possibilities for public housing and communal care. If the tech zillionaires that run this city would just be forced to contribute a tiny portion of their earnings to city services, we could easily have free public transportation and housing for everyone. Instead Metro ends the Ride Free Area due to a funding shortage after a tax repeal, and homelessness and housing instability soar to record highs. If this isn’t dystopia, I don’t know what is.

I go on walks. Mostly around Capitol Hill, where I live, but also to other neighborhoods. Once a week I have an appointment in Eastlake, so I walk down the hill and over on Lakeview, where I see the backsides of everything. For several years, I would pass a muddy area with overgrown weeds on a small cliff between Lakeview and the ditch next to the highway, and in that little patch of land there were people creating a home. Some of them were living in tents, some were sleeping in piles of belongings exposed to the rain. Maybe the luckier ones were in campers nearby. It was a culture of drugs and desperation, but it was a culture.

I always feel a kinship with anyone struggling desperately to get by, and so even though I was not a part of this culture I felt something like hope when I walked past. Hope that this city could still be a place where people on the fringe can survive. Isn’t this why we come to cities?

So sometimes this was my favorite part of the walk, just seeing people and saying hi. Then one day I walked by and there were giant tractors tearing everything up. At first I felt a panic because what if people were still sleeping in the grass like they usually were, but then I just felt an incredible anger like I wanted to push the tractors over the cliff, and then of course this feeling faded into the usual helplessness. Once the rage would have lasted longer, but that was before twenty years of debilitating chronic health problems that brought me back to the city where I first found calm. But here so often it feels like the middle-class imagination has conquered everything, and even if this doesn’t include my dreams it means I rarely feel connected to something larger than loss.

Now there are nine gray rowhouses overlooking the ditch next to the highway. Each one sold for $895,000. Most of them look as bland as before they were inhabited, but one has a cute little metal table outside with chairs, and pots of chrysanthemums. One time I saw the guy who lives there and I waved, but he didn’t wave back. Still I have a fantasy that he’ll invite me in, we’ll cuddle in bed and I’ll tell him about the people who used to live where he lives now, and maybe he’ll agree with me about the injustice, even though he’s part of it. Even though all of us are part of it, especially those of us with the privilege to live in a place that won’t be taken away.

When I hear the phrase that Seattle is a great literary city, I want to scream. Because when people praise what Seattle is now, it feels like they’re praising displacement, homogenization, the streamlining of the imagination to become a tool of social, cultural and political obliteration. I don’t believe that literature is automatically a force for good, especially if it participates in the self-congratulatory boosterism that celebrates Seattle as it is now. If we cannot critique what we love, then we don’t really love it.

If this is a great literary city, how do we expose all the layers of violence so we can imagine something else? How do we write what we really feel, so we can feel what we really need? How do we use language to expose hypocrisy rather than camouflaging harm? I want to live in a city that doesn’t destroy the lives of the people who are already the most marginalized by systemic and systematic injustice. This may be too much to ask of literature, but it’s not too much to ask.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore is the author of three novels and a memoir, and the editor of five nonfiction anthologies. Her memoir, The End of San Francisco, won a Lambda Literary Award, and her anthology, Why Are Faggots So Afraid of Faggots?: Flaming Challenges to Masculinity, Objectification, and the Desire to Conform, was an American Library Association Stonewall Honor Book. Her latest title, the novel Sketchtasy, was one of NPR’s Best Books of 2018. She is currently at work on a new anthology, Between Certain Death and a Possible Future: Queer Writing on Growing Up with the AIDS Crisis, and her next book, The Freezer Door, a lyric essay on desire and its impossibility, set in Seattle, will be out in fall 2020.