An Essay from “Seismic” by Wei-Wei Lee

September 30, 2020

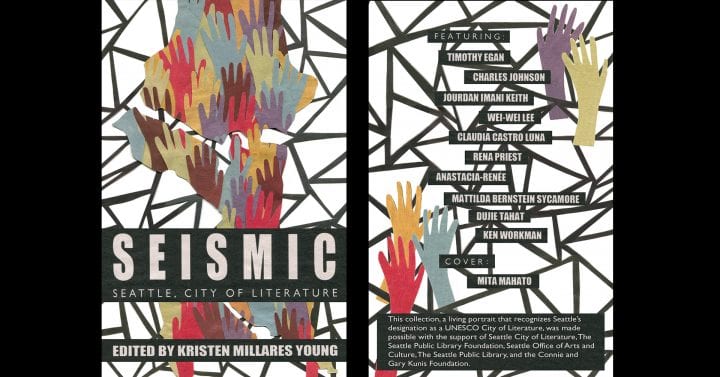

This essay appears in Seismic: Seattle, City of Literature, an anthology edited by Kristen Millares Young, featuring writers from all across the city. Seattle was designated a UNESCO City of Literature in 2017 and has been working as part of the international network since then.

Seismic is a collection that asks writers to consider what the designation means for our city and how literature might be an agent of change. Learn more and download your copy now!

By Wei-Wei Lee, 2019/20 Seattle Youth Poet Laureate

There’s an East Asian tradition my parents performed for us, me and my sisters, when we were very little. The word in Mandarin is 抓週, and there’s no good translation for it other than one suggestion I scraped from the internet: drawing lots.

The tradition goes thus: when the new baby is about a year old, a small ceremony is held where the baby is surrounded with representative objects, and whichever the baby grabs is indicative of who they’ll grow up to be. As lovingly and cheerfully recounted by my parents at just about every family gathering, my eldest sister went for the stethoscope and book, indicative of academia, a future in medicine. My second sister grabbed a book and pen, indicative of academia, creativity, artistry.

I crawled for a New Taiwan thousand-dollar bill and turned right around to give it to my mother. This is the story they love telling the most. Indicative of a life of fortune and plenty. Something in business, perhaps? A career that would bring wealth.

There is a reason I found drawing lots a fair translation. We were drawing our lot in life, or so the tradition goes. Of course, it’s just a household ritual, and people know not to put too much faith in it.

But there is a reason my parents still tell the story, and it isn’t just because it’s funny.

I was raised in an East Asian household, the product of two generations of hard work, sacrifice and academic excellence, in an Asiatic region that put a lot of focus on academia. My lot in life was to be something tremendous—a doctor or a lawyer, a dentist, professor or diplomat. Those were my parents’ dreams for me.

They told me I could be anything . . . as long as it put food on the table. I could study anything provided I could get a job afterward. Most everything had to have an outcome to it, a reward. Otherwise, what was the point? What was the point of learning piano if I couldn’t show off my skills to other people, relatives with children my age? What was the point of being good at English if I didn’t put it to good use by going to competitions?

(What was the point of being born, if I didn’t know due diligence?)

The lessons of success, clawed from the dirt and passed on parent to child, can fall into the realm of brutal efficiency.

I’ve loved writing since I was a child—have been writing since my stories found their way onto paper and into computers. My parents saw no reason to discourage this pastime as long as it came second to my studies. Of course, it came with the tagline that it wasn’t anything I should really pursue unless it proved to be a lucrative option. Again: efficiency. Why expend time and effort on something that wasn’t going to keep me alive? I have known, since I started writing, that until I managed to publish a bestseller or two, this would be nothing more than a mere hobby.

Poetry, however, has been a different beast altogether. For one, it was fostered in Seattle, encouraged in the loving arms of writing groups and workshops. For another, I was writing only for myself. I only wanted to capture raw feeling, persistent phrases that rustled around my head and demanded to be heard. I had no limitations, no expectations, no goals in mind. Neither, in fact, did my parents. I didn’t tell them I read at Benaroya Hall until after the fact, and I didn’t even tell them I’d entered the Youth Poet Laureate contest until I was home from reading alongside other finalists at Northwest Folklife. It was something just for the two of us, between me and the city of Seattle.

I grew up in Taiwan, and I’ve done some growing here in Seattle. Taiwan will always be my motherland—it’s the setting for all my memories, the foundation of who I am. It gave me discipline, identity and a story. But Taiwan tends to foster creativity for display, like something only to be lauded and put up in gleaming glass cases, and I am older than the girl who entered competitions just because it was, would be, an honor.

Seattle has given me freedom. It has afforded me the luxury of writing for the sake of feeling, without expectation or the pressures of succeeding, with my friends, classmates, school writers’ club and the Youth Poet Laureate Cohort. We trade our written stories across the table and listen spellbound. We read our poems aloud and sink into the words like a warm bath. We paint to provoke feeling. We speak and the words resonate. We create because it is in our nature, manifesting in our poetry slams, art galleries, and coffee shop concerts, from murals in Sodo to the painted array of electrical boxes in Lake City. We create no matter who we are.

To be here in this city is to be where creativity is cared for instead of being sown and grown and harvested until the fields go dry.

I never really thought I could be a poet, in every sense of the word, until I was on stage at Benaroya, although I’d been writing poetry for years by then. I hadn’t thought my poetry could amount to anything. I’d been trying to wrangle my parents’ expectations for so long that I didn’t realize I had my own expectations to contend with, too.

If you are, as I am, presently here in Seattle—whether you are passing through or staying put—remember that we each have a little magic, and the city brings it out in us. We are capable of creating such things as no one has ever done.

We are more than what people want to see, sometimes more than even we ourselves expect to see. We are not bound to the lots we draw.

Wei-Wei Lee is the 2019/20 Youth Poet Laureate of Seattle. She was born in the States but grew up in Taiwan and has only been stateside for four years. Seattle is the first city in the US she has ever known and loved. Though she first started writing around age eight, she only began writing poetry at fourteen—but she’s since fallen in love with it and hasn’t stopped. Poetry, for her, is largely based on pure feeling and imagery. In her work, she hopes to pay tribute to both Taiwan and America and do them proud.