Jill Lepore on Inheriting the Past

October 18, 2018

Harvard historian Jill Lepore is concerned about the brittleness of our politics—in her sold-out talk, which opened our Women You Need to Know Series on October 12, she argued that without historical context, our vision of the present has become impoverished and compressed into social media snapshots and bumper sticker slogans. What, she asked, can we gain by taking the long view of our history?

Over the course of an hour, Lepore’s presentation slid through two centuries of two-dimensional depictions of America—paintings, woodcuts, photographs, comics, and quilts—to show us how various peoples, past and present, have made arguments about their own power and political authority in America. Here are just a few notable images from her lecture, paired with quotes from the evening:

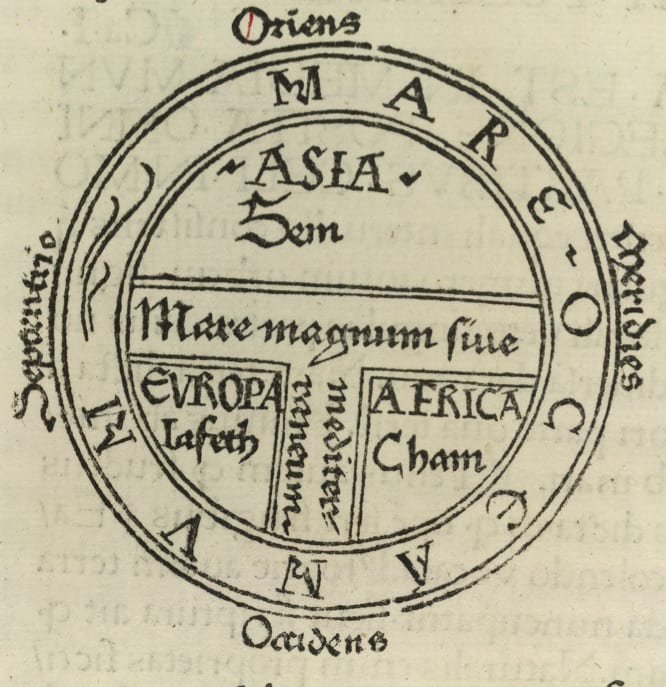

T-O map, originally drawn in the 7th century

“For centuries, Europeans understood the world as having been ordained by God in three parts; this is a medieval-Christian notion of the world—a T-O map that divides the world into three parts: Europe, Africa, and Asia, people of the three sons of Noah… This happens to have been the first map of the world ever printed, in 1472, after the invention of the Gutenberg press—and fourteen years later, it was completely obsolete. The epistemological crisis that this represents is earth-shattering. If your whole religious worldview involves a world divided in three because that’s what’s in the Bible, when a fourth part of the world suddenly appears, people don’t know what to do about that, especially mapmakers.”

Benjamin Franklin, woodcut, 1754

“This is a political cartoon that appeared in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette in 1754. Franklin was urging the mainland colonies to form a defensive union in order to defeat a coalition of Native peoples who were trying to oust the English from North America. Something that we often forget about this political cartoon is that in addition to it being a political cartoon, it’s also a map – we’re following the coastline here. What Franklin is playing on is this idea of the dissected map. Mapmakers in Europe at the time were so interested in explaining the authority of these nation-states to claim territory that mapmakers invented in the jigsaw puzzle in the 1750s. The first jigsaw puzzles were these dissected maps.”

Samuel Jennings, Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences, 1792

“It’s important to remember that, from the very beginning of the United States, the critique was always made that here was a people making claims for liberty and enslaving others. By 1792, that naked Native woman [that so often represented American colonists allegorically in earlier depictions] has gotten clothes; she’s no longer Native and is instead a white European-American woman who allegorically represents liberty. And, in this painting, she’s failing to emancipate the people who represent, allegorically, slavery. In particular, the African-American woman on the right with a handkerchief in her hair appears as a representation of the failure of the United States to achieve the liberty that its founding documents promise.”

America as a superhero, 1941

“The idea of America as an allegorical woman survives through World War II but is completely transformed by pop culture, particularly by comic books like Captain America (who is a loser and, I’m sorry, not worth our time). In 1941, Wonder Woman really is America—she’s that America that we saw as far back as that Dutch engraving in 1600, but now she has kick-ass superpowers, and she’s fighting for women’s rights and democracy. This idea that the U.S. had super powers comes out of its incredible economic strength, despite the Great Depression, because the U.S. didn’t suffer from the ravages of the first World War.”

Arcola Pettway, Lazy Gals (Bicentennial), 1976

“During the age that begins our era of political polarization, old symbols of the United States take on new political valence… Here’s that era of bumper sticker representation of political positions, but there remains this incredibly interesting and beautiful way, especially among folk artists—this is an African American folk artist who makes this flag for the bicentennial—of expressing a way of thinking about a political community in an entirely different mode from flags that have come before.”

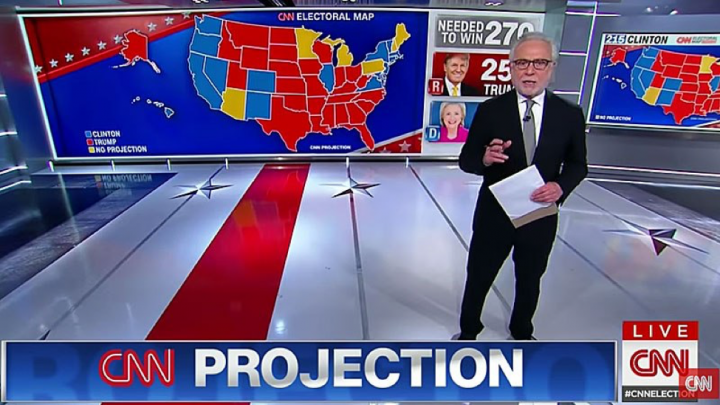

Election Night, 2016

“So much of our political theatre, our social movements, our political discourse, use history in ways that are shorthand for a genuine argument but that evoke a lot of things from the past… People are always saying to me: ‘You’re a historian, isn’t this unprecedented?’ And I always want to say, ‘A lot of this is precedented.’ It’s useful to think about where things come from and what traditions have been challenged successfully and which have not, which claims to power are effective, and which are not.”