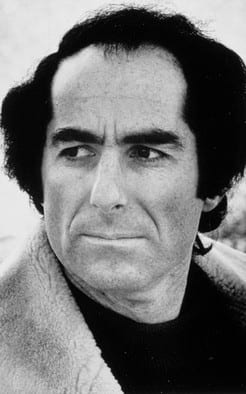

SAL/on air: Philip Roth

July 19, 2018

In our latest episode of SAL/on air, our literary podcast featuring talks from across Seattle Arts & Lectures’ thirty years, we hear from one of the pre-eminent authors of the 20th century—Philip Roth. He joined us back in October 1992 for a reading from his National Book Award-winning memoir, Patrimony: A True Story. Written with great intimacy at the height of his literary powers, Patrimony is Roth’s elegy to his father, who he accompanies, full of love and dread, through each stage of terminal brain cancer.

As he does so, Roth wrestles with the stubborn, survivalist drive that distinguished Herman Roth’s engagement with life, and his own anxieties around remembering the man with precision. “You mustn’t forget anything—that’s the inscription on [my father’s] coat of arms,” Roth writes. “To be alive, to him, is to be made of memory.” At the conclusion of Roth’s reading, he takes questions from the audience.

Sadly, Roth passed away in May 2018 at the age of eighty-five, after a long and vital career of investigating what it meant for him to be an American, a Jew, a writer, and a man, through many different masks. He once said: “Updike and Bellow hold their flashlights out into the world, reveal the world as it is now. I dig a hole and shine my flashlight into the hole.”

Listen to the episode here on lectures.org, or wherever you get your podcasts (and don’t forget to “like” and subscribe!). But, if you don’t have time to listen to Roth speak, here are some highlights from the event.

Lecture Highlights

On the Roth family’s origins

The Sender Roths, both about thirty, arrived in Newark about a hundred years ago with three small boys and no money. Not a cent. The language they spoke was Yiddish. My grandfather had been trained as a child to be a rabbi, and so he knew Hebrew as well. He got a job at a hat factory. . .

Like three-quarters of the children of Newark’s enormous new immigrant population, three-quarters of them, my father did not attend school beyond the 8th grade. He left 13th Avenue School at the then-legal school-leaving-age of fourteen to work in the hat factory beside my grandfather.

On giving his father the news of his diagnosis

Of all things, [my father] smiled. A wry half-smile really, that worldly-wise, heartbroken smile that says, But of course. He put his hand to the base of his skull and feeling nothing unusual there, smiled again.

“Well, everybody leaves this earth in a different way.”

“And,” I replied, “everybody lives on it in a different way. Everybody’s battle is different and the battle never ends.”

On his father’s stubbornness

He had no idea just how unproductive, how maddening, even at times how cruel his admonishing could be. He would’ve told you that you could lead a horse to water and you can make him drink. You just hock him and hock him and hock him until he comes to his senses and does it. Hock—a Yiddish-ism that in this context means to badger, to bludgeon, to hammer with warnings and edicts and pleas. In short: to drill a hole in somebody’s head with words.

On being a realist

Ever since my mother’s death, each time he came to stay with us in Connecticut, he had something with him: in a paper bag, or a shopping bag, or in a little plaid valise. . . It was usually a present for him and my mother from me, or from Claire and me, that now, years later, he was returning, as though what they had been given had only been on loan or left there on storage. “Here are those napkins.” Or, “here are the placemats.” Or, “here are the steak knives. . .”

Item by item, I took it all back like a well-trained refund clerk in a first-rate department store—but wondering if, perhaps, what he was thinking while he wrapped these gifts in old newspaper and stuffed them in cartons of every description, was that this way we wouldn’t have too many of his possessions to bother about after his funeral. He could be a pitiless realist, but I was not his offspring for nothing, and I could be pretty realistic too.

On his father’s mordant humor

[The doctor] explained where the tumor was situated and where it was pressing into the brain. He showed us on the back wall of the skull where he could cut through to go in to remove it. “We’ll just lift the brain a little here and take out what’s growing underneath it,” he said.

The thought of his lifting my father’s brain staggered me. I hadn’t believed you could do such a thing to a brain without inviting disaster, and for all I knew, you couldn’t.

“What do you use to go in there,” my father asked. “General Electric or Black & Decker?”

On the relative ease of writing Patrimony

Even now, I’m surprised to remember the resemblance there was between the unequivocal way this book was written and the problematic, addled way other books of mine have been. I wrote this book, I’m amazed to say, the way Chekhov is said to have written his stories—the way a bird sings. And yet no experience to which I’d ever looked for inspiration was anything like so dreadful to me as this one.

On why he chose to chronicle his father’s death

I was writing not because it was the only effectual thing I could think to do, but because I knew I could do nothing to alter anything. It was out of this powerlessness that I began to write. The writing did not make me less powerless; it made me utterly powerless. More powerless even than I might have felt had I not been saddled with the predilection to seek in words for some hint of the way things really are . . .

This incomprehensible thing that couldn’t possibly be happening, this far-fetched fairytale entitled “Father Dies,” had to be happening if words that were accurate could be found to describe it. Through writing, I imposed upon myself belief.

On trying to distinguish what’s permissible to write about

It isn’t that something is too vulgar to write about—it’s that you’re writing about it vulgarly is the problem. Nothing is too vulgar to write about.