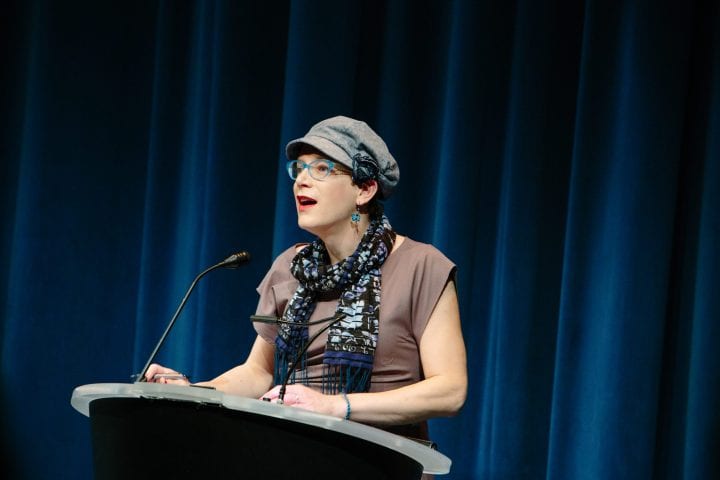

Introductions: Stephanie Burt

October 24, 2017

On Monday, October 9, at McCaw Hall, the electrifying Stephanie Burt read us poems from her latest, Advice from the Lights, schooled us on indie rock, and gave us some stellar new reading recommendations to stack our shelves with. SAL Associate Director Rebecca Hoogs introduced and interviewed Stephanie for this event, which opened SAL’s 2017/18 Poetry Series.

By Rebecca Hoogs, SAL Associate Director

It is a delight to welcome one of poetry’s brightest lights, Stephanie Burt, to the SAL stage. Burt is the author of four collections of poetry, including the just-released Advice from the Lights, and several volumes of criticism, including last year’s The Poem is You, a collection of 60 poems from the last four decades accompanied by illuminating essays.

Burt’s writing, especially in the latest collection, deals with an array of hoods: childhood, girlhood, parenthood, selfhood. I scribbled so many kinds of hoods in the margin that I grew curious—what does hood as a suffix actually mean? It is, of course, not a covering, but a state of being. And digging into the etymology, I found it literally means “bright appearance.”

Burt’s poems in this collection reveal not one state of being, but many states of being, many states of many beings. And isn’t that the pleasure of poetry? Of getting to have it both ways? Or double meanings? Triple? Of getting to be so many places at once and so many selves? “‘Few of us are finished,” Burt said in an interview. “None of us ever find moments when we have at last enunciated the single, true, real, authentic, satisfactory self: Instead we can work to articulate that self as it changes and multiplies and evades us, whether or not we do so with our changing bodies’ physical appearance, whether or not we do it in poems.”

The new book moves from persona poems—using objects like kites, or animals (many of whom will be familiar to my fellow parents who, like me, spend a lot of time at the zoo)—to poems that depict a particular year, mostly set in the 80s, to look back, or look within, to resist the trapper keeper of society and its three-ring binding. And though Burt describes her particular experience of feeling like a girl in a boy’s body, most of us can relate to feeling out of place, out of sorts, and to desperately wanting an oversized ESPRIT sweatshirt to crawl into. This dark room might, in fact, be such a space.

Bookforum called Burt “an ideal guide. . . through contemporary American poetry.” And I would add that whether she is shining her guide’s light on other poets across the aesthetic spectrum via criticism or—soon, as poetry co-editor at The Nation—or on the world through her own poems, we need the force for good and positivity and poetry and beauty that is Stephanie Burt.