On Claudia Rankine and Citizen

May 20, 2016

By Gabrielle Bates

“The route is often associative.”

—Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric

[Yes, and]

When I was a little girl in Birmingham, Alabama, wracked with shame over some transgression I can no longer remember, I asked my father how, when faced with a choice, to know which decision is the right one. He told me to figure out which choice would take the most courage, and then do that.

To this day, it’s the best advice I’ve ever received. Few writers have reinforced my resolve to follow it like Claudia Rankine.

[+]

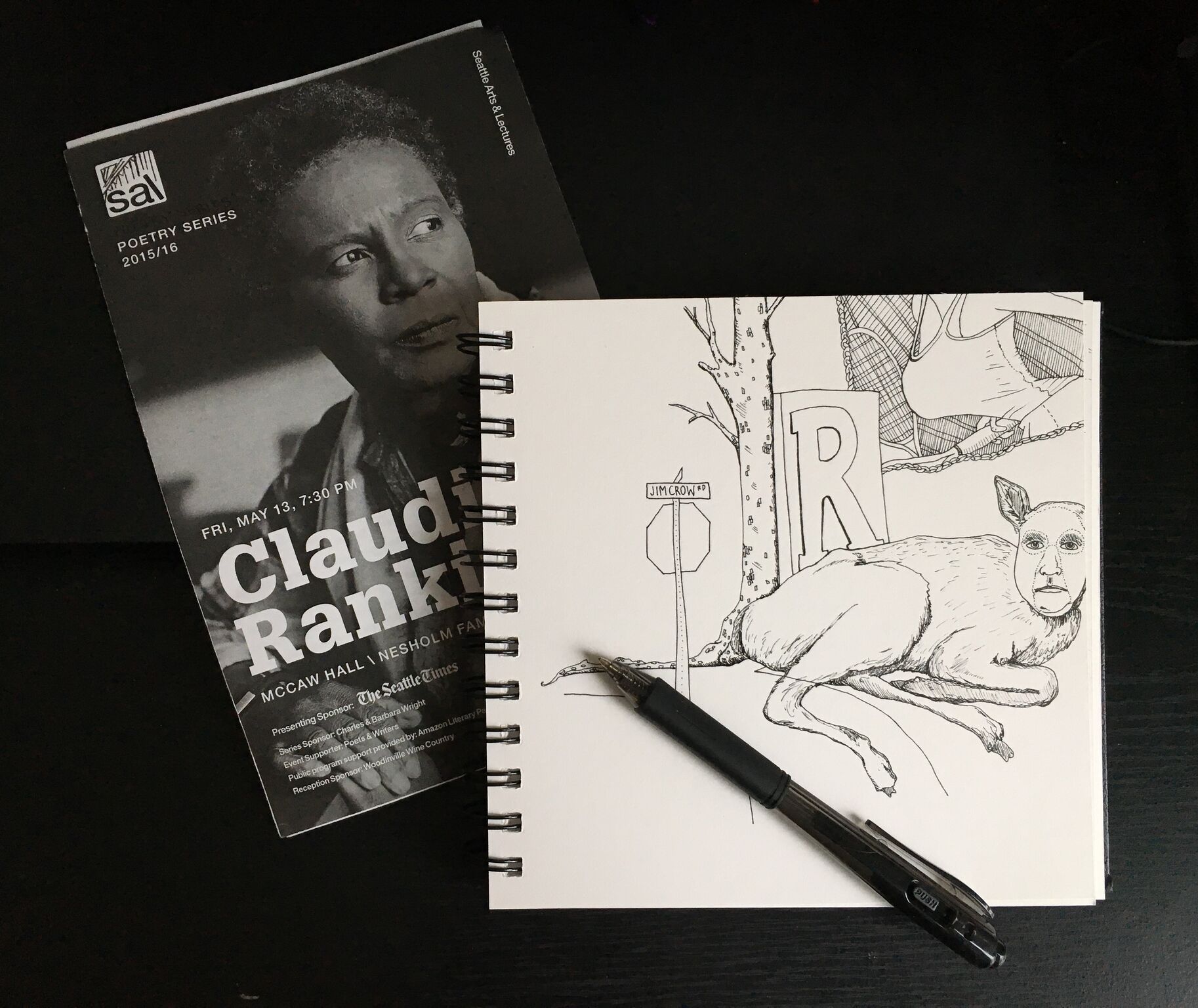

Claudia Rankine organized her May 13, 2016 lecture around the visual images that appear in her genre-defying Citizen.

Behind her podium, a photograph is projected. A street-sign in a suburban neighborhood: Jim Crow St. It’s not Photoshopped. You can move there.

“Our culture is based on segregation,” Rankine says. ‘Segregation Forever’ is in many ways our real national anthem.”

She changes the slide.

[+]

I’ve been drawing a lot of chimerical figures lately.

[+]

I have a friend who begins class by asking her undergraduates to write on the board an emotion. How did reading this book make you feel?

What I remember most about reading Citizen is sitting on the east-bound 44, getting heated over all the insults and injustices Serena Williams—as a black woman excelling in a traditionally white sport—has had to face in her tennis career.

The word I would write on the white board is probably “anger.”

Reading Citizen made me angry—angry at all the injustices, great and small, so many people have to face every day in this country solely based on the color of their skin. And angry that this system which requires black people be viewed as somehow less human, less trustworthy, less lovable and worthy of respect, thrives on the pretense that this system is “protecting” white people—people like me. In reality, this system hurts all of us.

[+]

This, Rankine gestures, is the photograph circulated in the New York Times, Washington Post, etc. of the Rutgers women’s basketball team in the aftermath of Don Imus’s infamous racial slur on national radio. The image shows five young black women, and six uniformed bodies. A large red R covers up a fifth player’s face.

Why that move? Why that erasure?

[+]

In a recent New Yorker essay on Adrienne Rich, Rankine writes, “There are many great poets, but not all of them alter the ways in which we understand the world we live in; not all of them suggest that words can be held responsible.”

[+]

Last Christmas Eve, I visited the Midway Plantation slave cemetery in Nashville, Tennessee. It is located in a slice of road median. Blink and you’ll miss it. This is one of the grave markers. Opulent estates are visible in every direction. The plantation owner’s original ante-bellum home is now the centerpiece of The Brentwood Country Club.

[+]

Citizen is a book that rewards multiple readings. Indeed, it practically demands them. The first encounter, in my experience, is raw and emotional. There’s little energy available for cool literary analysis. But subsequent readings opened my eyes more to the elements of craft at play in the book: how Rankine weaves anecdotal vignettes, visual art, sound play, and a wide array of poetic and rhetorical techniques to create an event on the page.

In Citizen, Rankine chooses a rhetoric of accumulation (the “yes, and” construction over the “yes, but” construction), employing this phrase as a stitch that reaches subtly across sections, constantly tying disparate anecdotes and modes together as part of a larger accumulation of experience. It’s a propulsive rhetorical construction that simultaneously reaches forward and backward into the text.

The “yes, and” is one small example of how form and content work in tandem in Citizen. And this tension between the simultaneously recurring past, present, and future is just one of the many tensions Rankine uses to keep readers emotionally and intellectually invested as the book unfolds.

[+]

Rankine flashes a new photo on the screen, the original version.

The sixth Rutgers player, whose face was strategically covered by the media with a big red R, unlike the players whose faces are visible, is white.

Why erase her from the story? To protect the myth that racism only affects black people?

[+]

When I visited Kehinde Wiley’s exhibit at the SAM a few months ago, I couldn’t stop staring at this sculpture. It’s called “Bound.”

[+]

When asked the impossible question, “What has made Citizen so successful?” Rankine mentions how iPhones have changed our culture in that people (particularly white people) can now see for themselves what black people go through in this country. White people no longer have to take anyone’s word for it; they can see the horror and injustice for themselves.

Citizen encourages readers who might be tempted to dismiss the injustice under scrutiny as “subjective” to see and experience, drawing their own conclusions. Behind the intellectual and emotional whirlwind of the language event that is Citizen stands the real world. Real, undeniable, sickening injustice you can fact-check. We can go to the video footage. We can watch the white line judges make bad call after bad call against Serena Williams, costing her the US Open. We can watch the lives of Americans—fathers, sisters, children—being taken for no other reason than their existence made a white person suspicious, angry, or afraid. It happens shopping at Wal-Mart. Playing in the park. Driving home from work.

At the end of her lecture, Rankine shows a short film collaboration she made with John Lucas, which includes compilations of exactly this kind of video footage. Many of the clips are immediately recognizable to anyone who has been keeping up with the news the last few years. It is one of the hardest things I’ve ever watched. I will myself not to sob aloud, but the tears come.

Another crying white woman is not what this country needs.

[+]

The last question posed by an audience member to Rankine in the Q & A is, more or less, “What can we do?”

Each time someone in our lives says or does something racist, we’re presented with an option, and the option is to speak up or not. When our co-workers do it. When our dad does it. When we witness a cashier. A teacher. A boss.

Stay proximate, Rankine says. And speak up.

Figure out which choice would take the most courage, and then do that.

These are the little moments that, when allowed to continue, become lives.

This is the truth Citizen lays bare, the charge I’m left holding—tennis ball, road sign, big red R—in my throat.

Gabrielle Bates is a Southern writer living in Seattle, where she serves as coordinating editor of The Seattle Review and twitter editor of Broadsided Press. She is an Indiana Review Poetry Prize finalist, winner of Gigantic Sequins’ poetry comic contest, and her work appears or is forthcoming in Best of the Net 2015, Black Warrior Review, New South, Rattle, Guernica, Southern Humanities Review, Radar Poetry, and Thrush, among other journals. She will graduate with her MFA in poetry from the University of Washington in June 2016. She can be found online at www.gabriellebatesstahlman.com or on twitter (@GabrielleBates).