Tyehimba Jess and the Voice of the Interior

February 22, 2018

Seattle poet and educator Quenton Baker, whose work focuses on anti-blackness and the afterlife of slavery, writes below on Tyehimba Jess’s Pulitzer Prize-winning collection Olio. Jess’s work weaves sonnet, song, and narrative to examine the lives of African American musicians from the Civil War era on, in an effort to understand how these performers met, resisted, and complicated attempts to minstrelize them.

Tyehimba Jess will read from and discuss Olio on Sunday, Mar. 4, at McCaw Hall. The event will be followed by a Q&A moderated by Anastacia Renée, Seattle’s Civic Poet. Tickets are still available here.

By Quenton Baker

In the opening line to his brilliant In the Break, Fred Moten writes, “The history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist.” It is no secret that the black body was (and remains) commoditized and objectified, but what has been made secret, or perhaps secreted away through the occluding nature of anti-blackness, is the reality that Moten and many others reveal and make plain: blackness has always found a way to create under constraint, and those methods and modes of creation have been in the service of a profound and necessary resistance.

Tyehimba Jess, in his monumental, Pulitzer Prize-winning collection Olio, documents the resistance of several late-19th and early-20th century black artists and musicians—Jess reclaims their work, their voices, their songs and, in the process, gives his characters back to themselves. Olio spans an impressive range of post-Civil War black icons, from the sculptor Edmonia Lewis to performers like Millie and Christine McKoy and Sissieretta Jones. Jess deploys an equally impressive range of poetic forms for these diverse voices to inhabit. Syncopated sonnets and double-columned telestitches highlight an endlessly inventive mélange of poetic craft, all meant to call these characters and their stories into sharp focus.

Throughout Olio, Jess is on a mission to map the agency and dignity of these artists, to demonstrate the ways in which they are each, as Jess puts it in “Edmonia Lewis: Provenance”: “the sound of one / mallet against history’s / pale fist.” It is an excavation of song, a tracing of the thick musicality of black performers plying their craft, mostly, in the pre-recording era. It is easy, perhaps, to dismiss the complexity of these characters, to lose sight of their power and pride amidst the pain of oppression, the obliteration one experiences under social control, especially when we lack their stories in their own voices. In Olio, Jess, as black folks often do, finds a way to offer redress to these characters, and to himself, when it otherwise would not exist.

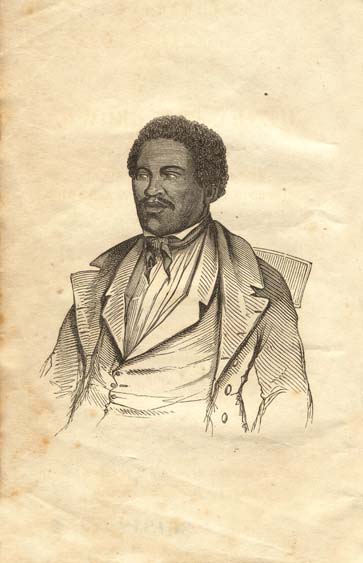

Edmonia Lewis (1870), Albumen print

Each one of Olio’s individual sections is worthy of and rewards close examination, but none stands out more to me, than Jess’ section on the performer Henry “Box” Brown. Henry “Box” Brown was born into slavery around the year 1815 on a plantation in Virginia. Brown’s wife, Nancy, and their three children were undoubtedly the most precious part of his life, and when they were sold to another plantation without warning in 1849, Brown was devastated.

Never one, previously, to agitate overtly against his alienated position as an enslaved person, Brown underwent a dramatic transformation that led him to plan a fantastically daring escape. In order to find freedom, Brown used $83 he had saved up to mail himself in a three-foot-long box to abolitionists in Philadelphia. He survived the journey, despite being turned on his head at one point, and came out of the box signing a hymn, as the story goes. It is one of the more miraculous flights of slavery in American history but perhaps what took place after his risky escape is more astonishing.

After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1851 was passed, and Brown survived a brutal capture attempt by a slave catcher, he left the United States for London, and went on to enjoy a long international career as a speaker, mesmerist, and magician. To Brown, the concepts of slavery and freedom, as Martha J. Cutter writes in her exploration of his life, “were entities to be conjured… and he drew on both subversively to create symbols for his performances of magic.” Brown would use the very box he escaped in during his magic shows, restaging his escape and triumph. The box came to symbolize, as Cutter points out: “not the living death of slavery but a plural and open space of miraculous transformation, of destruction and also resurrection.”

And the Henry “Box” Brown of Jess’s Olio lives in that plural and open space, conjuring the symbols of his own freedom as a repudiation of what Jess calls the “literary bondage” created by the central “Henry” persona in John Berryman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Dream Songs, who is at times in blackface and speaking in minstrel dialect throughout Berryman’s collection.

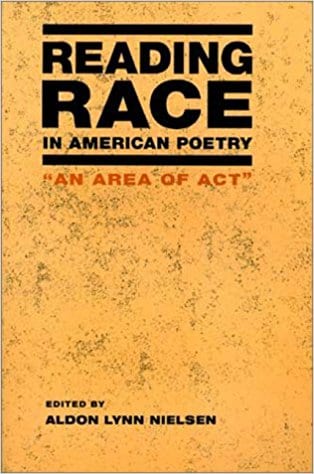

Henry “Box” Brown (1849)

Berryman’s use of blackface in The Dream Songs typically alternates between being ignored, sped through or inadequately defended by critics. Berryman himself never conjured up much of a defense or reason for its inclusion, other than a couple brief mentions in an opening note to The Dream Songs and some very unsatisfying interview responses. Absent of any real insight from the poet himself, we are left, as the scholar Aldon Lynn Nielsen has done, to look at Berryman’s use of blackface within the framework of white discursive traditions and anti-blackness.

In Reading Race, Nielsen writes: “The Dream Songs are the not wholly conscious imaginings of Henry, the white man, and this dialect is an enactment of the white mind playing at blackness within its system of stereotypes.” Indeed, Berryman is imagining an imagining—he cannot escape the terra firma of the white imagination in his attempt to subvert or overturn certain agreements of white discourse, as he has no access to any one of the innumerable actual black dialects, or any genuine configuration of actual black interiority, and can only ape and mimic in the patterns of a pre-imagined believed-to-be-black dialect: minstrelsy.

Adrienne Rich, a staunch supporter of The Dream Songs offered this in Berryman’s defense in a 1969 issue of the Harvard Advocate: “A new language is evolving in the heads of some Americans who use English. Some streak of genius in Berryman told him to try on what he’s referred to as ‘that god-damned baby talk,’ that blackface dialect, for his persona. No political stance taught him, no rational sympathy with negritude. For blackface is the supreme dialect and posture of this country, going straight to the roots of our madness. A man who needs to discourse on the most extreme, most tragic subjects, has recourse to nigger talk.”

Of course, there is nothing resembling blackness or black speech in Rich’s rickety framework. Rich is speaking about a white poet accessing and interacting with parts of white discourse that the white imagination has tied to a specific location within itself and named blackness, a location that otherizes and oppresses actual black people but that has no ability to access or understand blackness as a real, multivalent, lived position in American society (or anywhere else, for that matter).

It is that real, lived position, that the Henry “Box” Brown of Jess’s Olio inhabits, and it is a real, lived-in language that Jess brings to bear upon Berryman’s misguided oneiric wanderings. In “Pre/Face” Jess puts Berryman and Brown nose-to-nose in a contrapuntal poem that uses text excerpted from Berryman’s introductory note to The Dream Songs. Brown, in response to Berryman’s matter of fact assertion that his character Henry is “sometimes / in / blackface,” claps back: “Let me say, / despite loss… I won my life. This story— / how a slave steals back his skin” and that, for those left behind, “Berryman can’t talk for them, / can’t tell my tale at all.”

Berryman is hoping, through his re-figuring of minstrel tropes and dialect, to get to the roots “of our madness,” as Rich points out. It is undoubtedly true that Berryman, writing these blackface poems at the height of the civil rights era, imagines himself as an agitator, a poet shaking up a staid white discourse to produce sympathy for the black fight for equality.

However, what Jess’s Henry “Box” Brown section makes plain, is that there is no possible path toward black humanity through minstrelsy or blackface. Minstrelsy only exists within the American context as a pathway to abrogate the humanity of black folks, to simultaneously validate all of the vulgar, fearful stereotypes required to hold an entire group of people as chattel and invalidate any concept or understanding of that group as socially alive, or belonging to society in any way other than as object. A benevolent use of objectification is not substantially different enough from a malicious use of objectification to warrant praise or even consideration. Jess shows us the actual antidote to the white discourse agreements that blackface creates and reifies. From “Freedsong: Dream of My Son”:

I’ve cleared the Hungry One’s claim: slavery.

From slavery, I don’t take nothing, see?

For no southland’s sake.

British is where I’m living; where I make

my fees and cop my promise. Where I be

cried myself awake…wishin’ I was dyin. But I had to make

my haul this way. In my bed, in my sleep,

when I put my head to dream,

maybe I’ll get to see my son…

us together. Never. I’m back, awake.

Free, black, and forty-one.

This, of course, is more than simple repudiation, or simple reclaiming. It is a total re-routing of Berryman’s blackface dialect, leading the reader away from the feeble, underfed signifying of Berryman’s Henry and into an actual, considered measurement of Henry “Box” Brown’s interiority.

The pivot from the minstrel dream within a dream to the longing dream of a fugitive slave for whom any possible reunion with his son is blocked by that fugitivity could not be more profound. Jess gives us an unsettling, uneasy glimpse at the joy and heartbreak endemic to black survival and the sort of insubstantial freedom that accompanies an escape from slavery—especially when one’s family is left behind.

Brown was magic, was the subject of his own magic, he was transformed, subsumed, resurrected from the social death and natal alienation of slavery into the unending fugitivity of freedom. Like all of Jess’s characters in Olio, Brown had a song, and he owned that song more than he owned his own skin. And in the singing of it, so much is unmade and redone, so much is let loose and let in from a necessary hinterland. From “Jubilee Indigo”:

How do we prove our souls to be wholly human

when the world don’t believe we have a soul?

How do we prove black souls holy and human

when the whole world swears we got no souls?

We hitch our voice to heaven’s sword-tongued plow

and sow the seeds of a righteous mission.

Quenton Baker is a poet and educator from Seattle. His current focus is anti-blackness and the afterlife of slavery. His work has appeared in Jubilat, Vinyl, Apogee, Poetry Northwest, The James Franco Review, and Cura and in the anthologies Measure for Measure: An Anthology of Poetic Meters and It Was Written: Poetry Inspired by Hip-Hop. He has an MFA in Poetry from the University of Southern Maine and is a two-time Pushcart Prize nominee. He is a 2017 Jack Straw Fellow and a former Made at Hugo House fellow, as well as the recipient of the James W. Ray Venture Project Award and the Arts Innovator Award from Artist Trust. He is the author of This Glittering Republic (Willow Books, 2016).